Aircraft Modes of Motion#

Hopefully the preceding was all revision, and we can use the theory to explore the Flight Dynamics of certain aircraft.

By ‘certain aircraft’, I mean that the equations of motion that we have developed are valid for symmetric, rigid, fixed-wing aircraft under certain flight regimes (small aerodynamic angles, flying in subsonic region, gentle manoeuvres). Aircraft that fall into this category generally exhibit the same five characteristic motions, which we will break down into longitudinal and lateral modes.

The transient response of the aircraft due to impulsive excitation has been explored, and it was shown to contain:

Two oscillatory modes present in the Longitudinal data

One oscillatory mode present in the Lateral data, and a further non-oscillatory mode (though it’ll turn out that there are actually more…).

As discussed in the preceding section, the modes of motion are related to the eigenvalues from the \([A]\) matrix.

The Longitudinal Modes#

There are two complex pairs of eigenvalues associated with the longitudinal equations of motion, and these confer to the two aircraft longitudinal modes - the Short Period Mode and the Phugoid mode.

Short Period Mode#

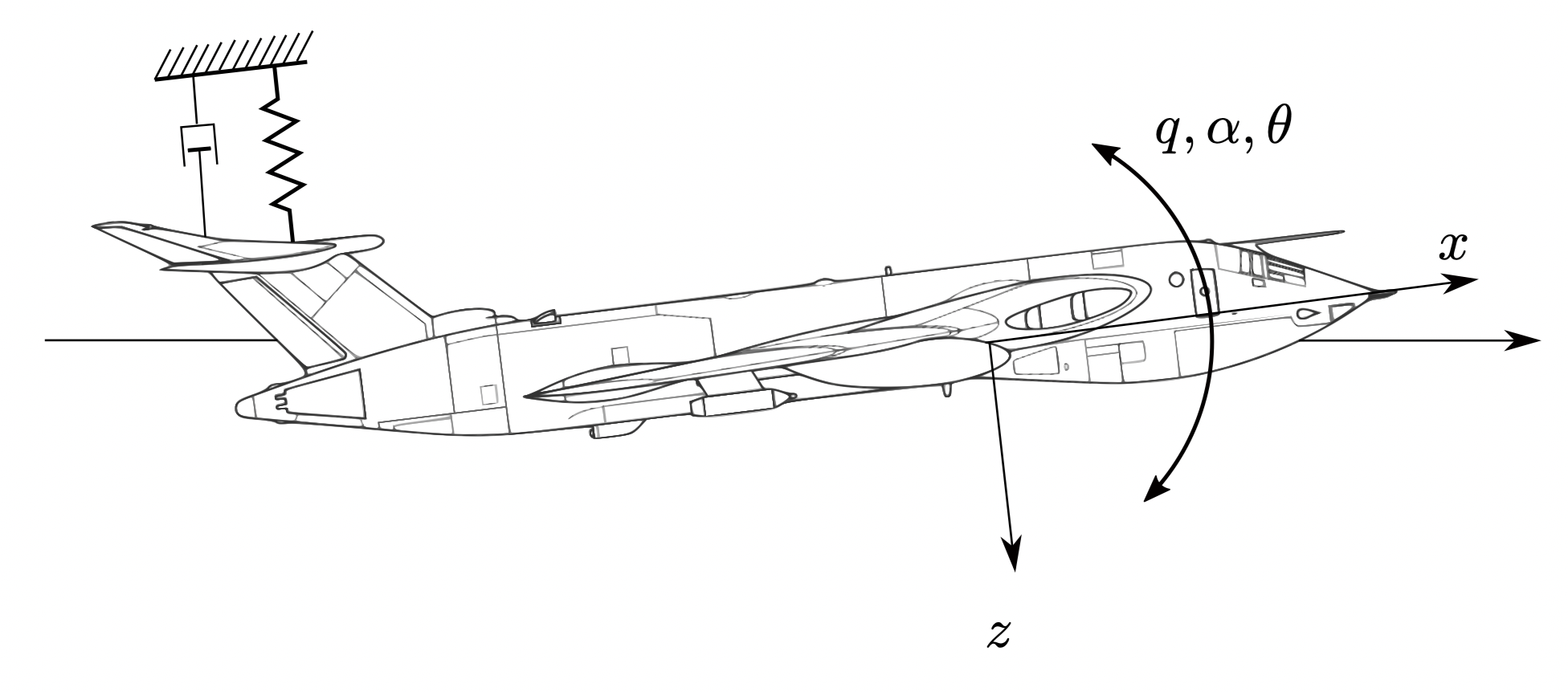

If a trimmed aircraft is subjected to a step input of elevator or a vertical gust, it will enter a pitching motion. The aircraft will tend to oscillate in pitch for a short period of time (meaning it is heavily damped). Consider the aircraft in Figure Fig. 57.

Fig. 57 Short Period Mode#

By comparison to the mass/spring/damper system, an analogy can be made to the short period pitching mode - the horizontal tail effectively provides stiffness (recall that the static margin was described as the pitch stiffness) due to the ‘weathercock’[3] tendency for the HTP to align the aircraft \(x\) axis with the incident flow. The aerodynamic and viscous forces created by the tail due to its motion under a pitch rate provide damping. A balance must be sought with damping as too much damping means that an aircraft’s pitch response is quite poor (thus sluggish, uncontrollable), whereas too little damping can cause a problems with overshoot in the short period mode.

The angle of attack changes rapidly, but there is usually no discernible effect on airspeed. For a small and/or manoeuvrable aircraft, this might have a period of less than a second, and for a larger or more sluggish aircraft it may be a few seconds.

Phugoid#

The Phugoid is an oscillation with almost no angle of attack change. There is little damping, and this mode can be unstable but the aircraft response is usually so slow that it is corrected by a pilot with little effort.

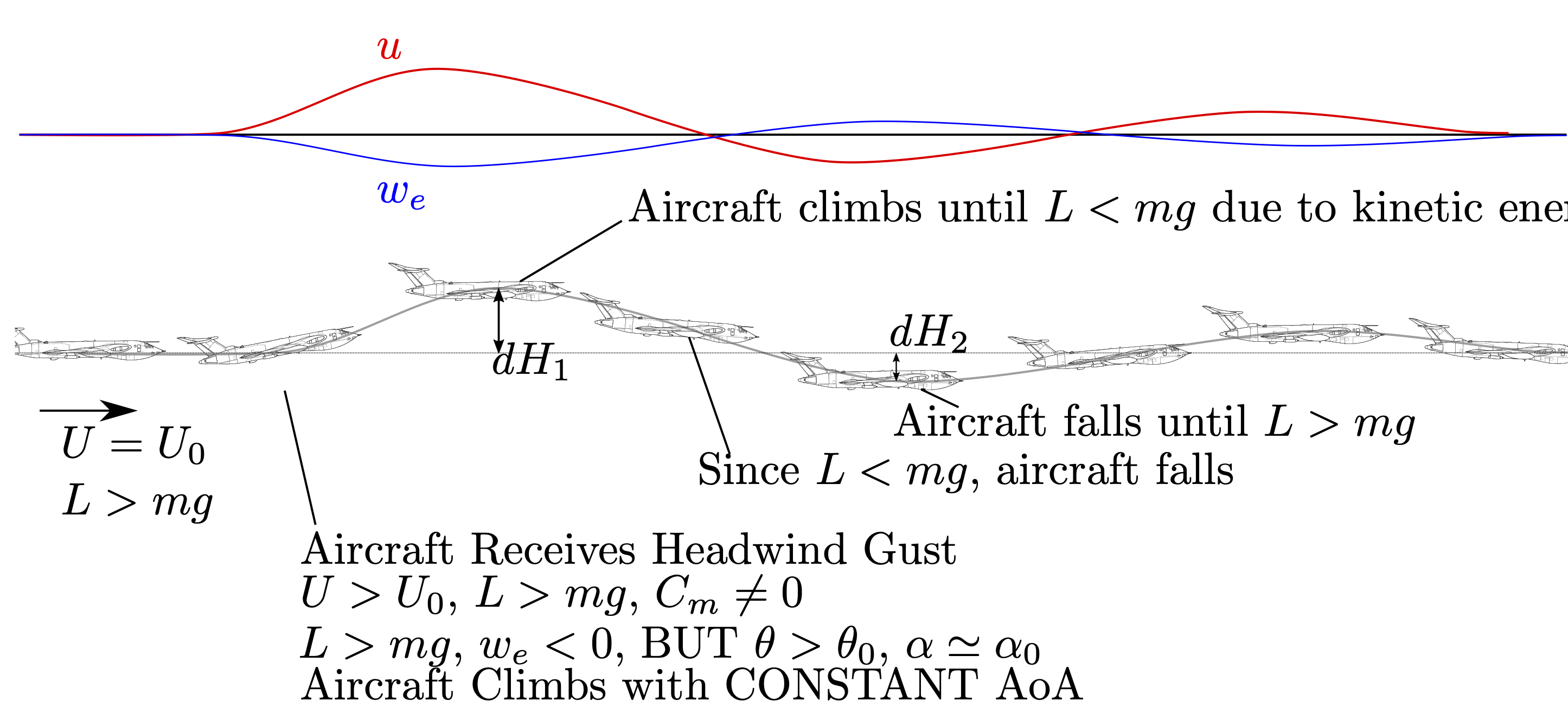

The physical mechanism of the Phugoid is effectively an exchange of gravitational potential energy and kinetic energy. If an aircraft receives a forward speed disturbance (a headwind gust), then the lift and pitching moment increase, increasing \(\theta\). Since \(L>mg\), the aircraft climbs giving a negative \(w\). The increased forward speed, reduced \(w\), and increased \(\theta\) mean that the aircraft climbs upwards with little to no change in angle of attack. The aircraft initially accelerates upwards whilst \(L>mg\), until \(L=mg\), at which point it has vertical kinetic energy - hence it continues to climb further whilst decelerating, with a reduction in pitch, until the vertical kinetic energy has all been converted into gravitational potential energy. At this point \(L<mg\), and the aircraft begins to fall, and pitches nose down - with a positive \(w\) and a reduced \(U\), again, the angle of attack is relatively constant. The aircraft falls to the point that \(L=mg\) and, again, beyond due to vertical kinetic energy - when it comes to a stop, \(L>mg\), and it begins to climb again, and so on. See Figure Fig. 58 for a schematic of this mode.

For a stable Phugoid mode (as most are), the oscillation is one of decreasing amplitude (by the definition of stable). Hence for the figure shown, \(dH_1>dH_2\). Operating in a vacuum, you would see no damping of this mode[4] - hence damping may be considered as a ‘drag damping’ as it absorbs some of the energy so the interchange between kinetic and gravitational potential is not perfect.\

Fig. 58 Phugoid Mode#

Etymology corner.

The term Phugoid was coined by Lanchester as “from the Greek \(\phi\nu\gamma\eta\) and \(\epsilon\iota\delta o\varsigma\) (lit. flight-like)”, but later in this work he goes on to state “the appropriateness of the derivation is perhaps diminished by the fact that the word \(\phi\nu\gamma\eta\) means flight in the sense of escape rather than the act of flying in the present signification”.

I figure that this shows that Lanchester thought of the term, and had been using it for a while, then realised (or, more likely, was told be his editor) that he had the etymology incorrect, but had been using it for so long that it had stuck.

I think it’s a great story, though.

The Lateral/Directional Modes#

There are three lateral/directional modes, which are described herein.

The Spiral Mode#

The spiral mode occurs, primarily, because of the means through which an aircraft changes heading whilst turning. If a co-ordinated banked turn occurs with increasing or decreasing radius, then this is a stable or unstable spiral mode respectively, with no oscillation. Hence with a turn of increasing radius, there is a negative real eigenvalue and with a turn of decreasing radius, there is a positive real eigenvalue. The unstable mode causes a turn of ever-increasing radius, hence the term ‘spiral’ mode.

When the mode is stable, the mode produces a turn of increasing radius until the aircraft is simply flying along a new heading (rectilinear flight may be considered as a turn of infinite radius). When the mode is unstable, a large roll angle may build up over time, without the pilot realising due to its slow build up.

Usually, the spiral mode is slow to the point that it is corrected by the pilot without conscious intervention. If a non-instrument rated pilot is flying in instrument conditions with little or no visual clues, however, large roll angles may build up to the point of a so-called graveyard spiral.

Why the spiral mode can be dangerous - the ‘graveyard spiral’

The human ear effectively has a fancy accelerometer pack, the ‘vestibular apparatus’, which comprises three fluid-filled canals aligned with three pretty-much mutually-orthogonal axes. The cilia inside these canals can detect the direction and magnitude of fluid motion above a certain threshold and hence correlate this to an angular rate (the brain is incredible - your central nervous system can perform integration and utilise Coriolis theorem even if you cannot). There are two further ‘otolithic’ detectors, which detect linear acceleration in the horizontal and vertical planes.

The human brain combines signals from the canals and the otolithic detectors to determine attitude in 3D space. Because only angular rates can be detected, if the aircraft is in a co-ordinated turn then the centripetal acceleration means that the otolithic detectors do not ‘see anything wrong’ - they tell the brain that it is aligned with the gravity vector (because it is aligned with the net vector from the gravity and the centripetal acceleration), and there is no angular rate detected because the angular rate is lower than the threshold in the inner ear.

Whilst the pilot does not feel anything wrong, the aircraft is turning into a tighter and tighter spiral until the centripetal acceleration is so large that it is felt through the seat (at which point something else may be felt through the seat of the pilot’s pants).

Without looking at the artificial horizon a pilot may feel the nose down motion and think that they are in a wings-level descent, in which case they will attempt to correct by pulling back on the yoke or joystick (increasing the elevator deflection) - which would be the correct action for a wings-level dive. However as we learned in Banked Turn, this will increase the load factor and thus further decrease the turn radius - tightening the spiral further and further, and increasing the descent rate more. The still-unaware pilot will pull back harder and harder, which only serves to make everyone onboard dizzy prior to the aircraft’s inevitable impact with the ground.

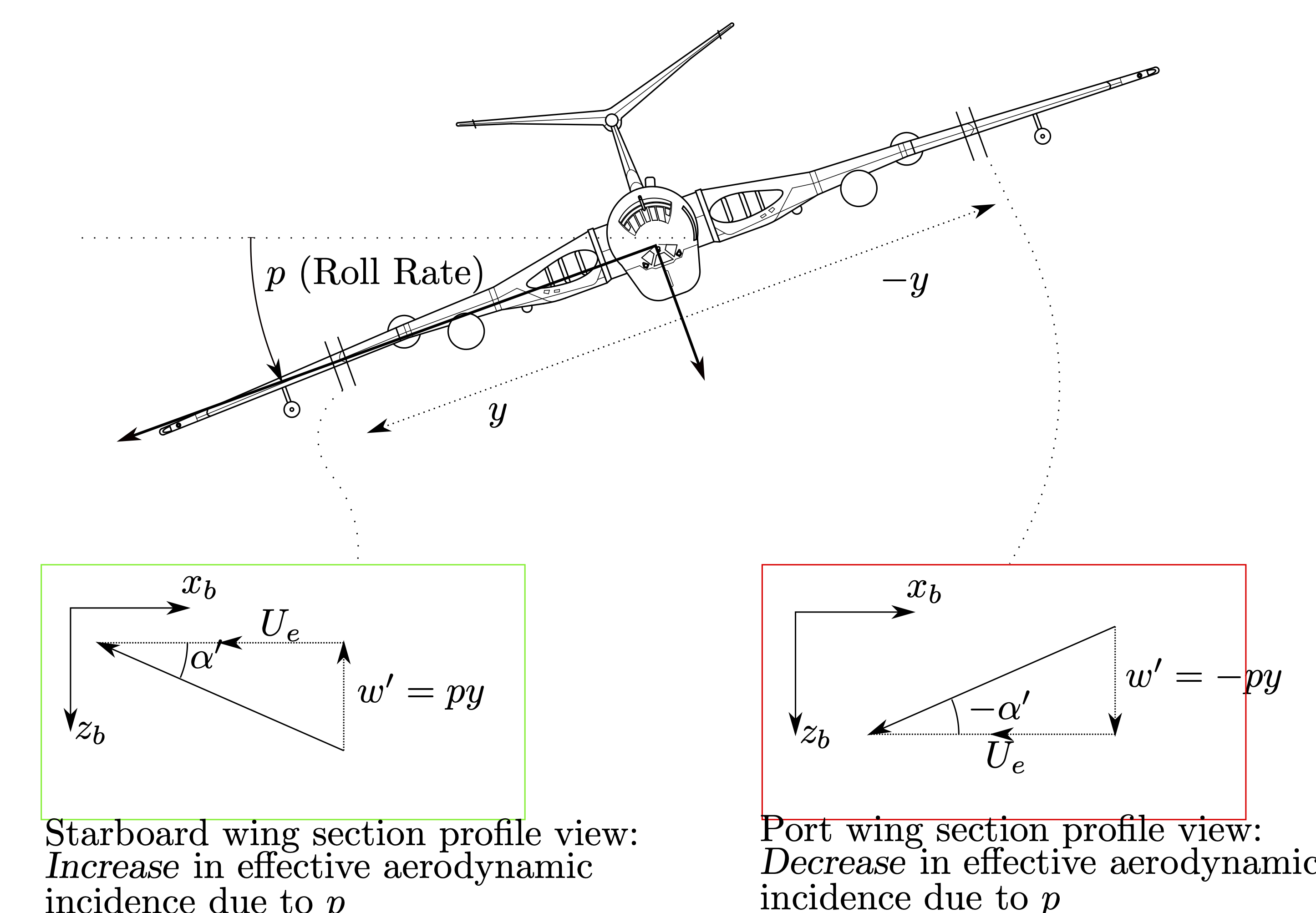

The Roll Mode#

The roll mode is fairly easy to understand, and is a stable and fast mode, and arises as a consequence of the aircraft roll rate, \(p\). An aircraft with a positive roll rate will lower the starboard wing, and raise the port wing. This creates a spanwise-varying upwash and downwash on the two wings as a consequence of the tangential motion. This will always create an increase in incidence in the ‘downgoing’ wing, and a decrease in incidence in the ‘upgoing wing’. The local lift varies proportionally to the incremental incidence, and this creates a restorative moment. See Figure Fig. 59.

Thus, for any roll disturbance, the aircraft will tend to arrest the consequential rolling motion via what is often terms ‘roll damping’. So the roll mode is always stable.

Fig. 59 Roll Mode#

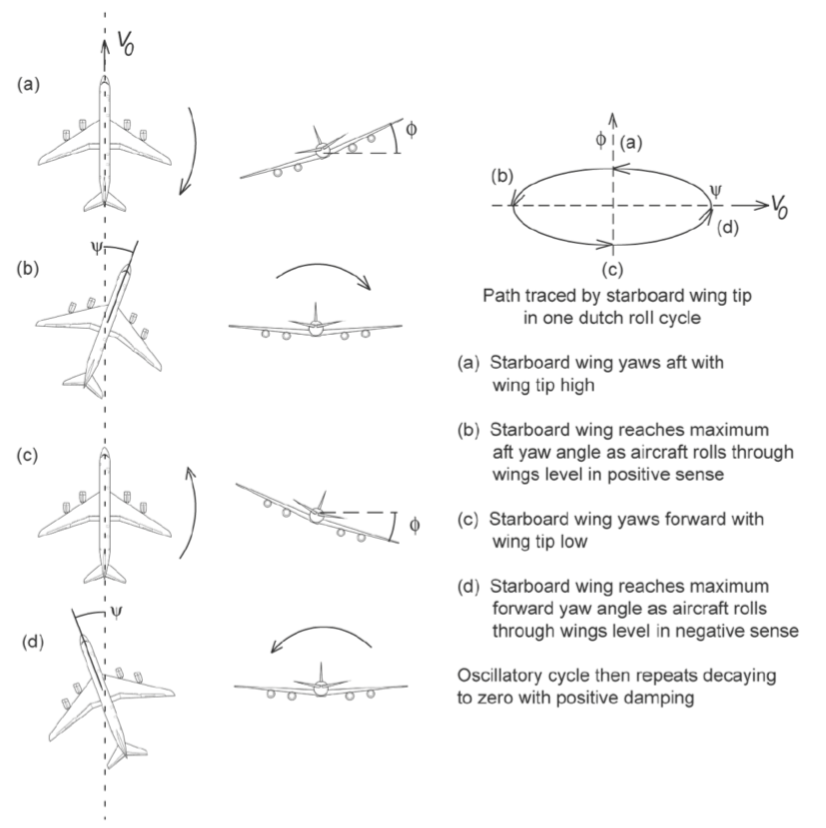

The Dutch Roll Mode#

The Dutch Roll mode is difficult to visualise from words on a page[5], but the description herein attempts to explain it. This characteristic motion is a combination of sideslip, yaw, and roll. The aircraft sideslips in the opposite direction to its yaw motion, meaning that it maintains a relatively constant heading (track angle, \(\tau\)). As we have discussed, there is a coupling between sideslip and roll such that the relative velocities will cause an increase in lift on the wing on the side of the aircraft that it is sideslipping towards. (for an aircraft with a nose turned to starboard, it is sideslipping towards port, giving an increase in port lift, and a consequential positive rolling moment to starboard wing down).

This mode tends to be stable, and is lightly damped. In ice-skating, an technique whereby skaters stay on the edge of their blades, swinging their weight from side to side was called ‘dutch roll’ during the early 20th-Century - the name got given to this aircraft mode by early aerodynamicists (at least it’s a correct-ish term this time).

We can understand this motion by again utilising the ‘weathercock’ action of the spring to be modelled by a torsional mass/spring/damper system, aligned along the aircraft z-axis. After an initial yaw disturbance, the aircraft yaws in a damped oscillatory manner. As the wings ‘advance’ or ‘retreat’[6] the increase and decrease lift, respectively, and creating an oscillatory rolling moment. Neglecting unsteady aerodynamics (this motion is slow enough that we may consider quasi-steady aerodynamics), the roll motion lags the yaw motion by 90 degrees - the peak roll angle occurs when the aircraft is at \(\Psi=\Psi_e\), and the peak yaw angle occurs when the wings are level.

See Figure Fig. 60 for a visual of the characteristic motion. Hold your right hand out in front of you, with your thumb and little finger representing the port and starboard wing. Follow the motions of the aircraft, and try to recreate the Dutch Roll mode - ensure that you understand this.

Fig. 60 Dutch Roll Mode - borrowed from legacy material, original source unknown#

Summary of Aircraft Modes#

The modes are now easily discriminated by their characteristic behaviours and the main states which they excite. For the longitudinal modes:

Mode |

Characteristic |

Damping |

Period |

States |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Short-Period |

Fast, Stable Pitching Oscillation |

Heavily Damped |

A few seconds at most, usually less |

\(q, \theta, w\) |

Phugoid |

Slow, Stable OR Unstable Altitude Oscillation |

Light Positive or Negative |

Can be several minutes |

\(u, \theta\) |

and for the lateral/directional

Mode |

Characteristic |

Damping |

Duration |

States |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Roll |

Fast, Stable Rolling Motion |

Always Positively Damped |

Non-oscillatory, half amplitude very fast |

\(p, \phi\) |

Dutch-Roll |

Oscillatory coupling of sideslip, yaw, and rolling |

Positive or Negative |

Dependent on aircraft size |

\(\psi, \phi, v, p, r\) |

Spiral |

Slow, Stable OR Unstable coupling of roll/yaw |

Non-oscillatory |

Non-oscillatory, half/double amplitude can be several minutes |

\(\psi, \phi\) |