Defining Static Stability#

In the preceding module, the equilibrium steady flight condition was utilised

inherent in the analysis but not explicitly stated is the further consideration that in order to stay at a constant attitude (angular) orientation, the sum of the moments must also be zero

the equilibrium state is known as a trim condition. In the preceding chapter a short little about speed stability due to \(\frac{\text{d}D}{\text{d}V}\) was explored, but stability itself has not been defined not explored.

Nomenclature

Be careful - trim is sort-of loosely defined in aeronautics. For our purposes, ‘trim condition’ will mean one where the moments are zero. For a pilot, it is that but they actually mean where the stick force is zero due to careful adjustment of the trim tabs of the aircraft.

What is stability?#

For an aircraft, stability denotes the response of the aircraft if disturbed from an equilibrium or trim state.

Static Stability#

Primarily in this chapter, we will be concerned with the static stability of the aircraft which is defined as the tendency of an aircraft, following an external disturbance (e.g., a gust) to return to the undisturbed condition. There are three categories of static stability that we can describe qualitatively; statically stable, statically neutral, and statically unstable.

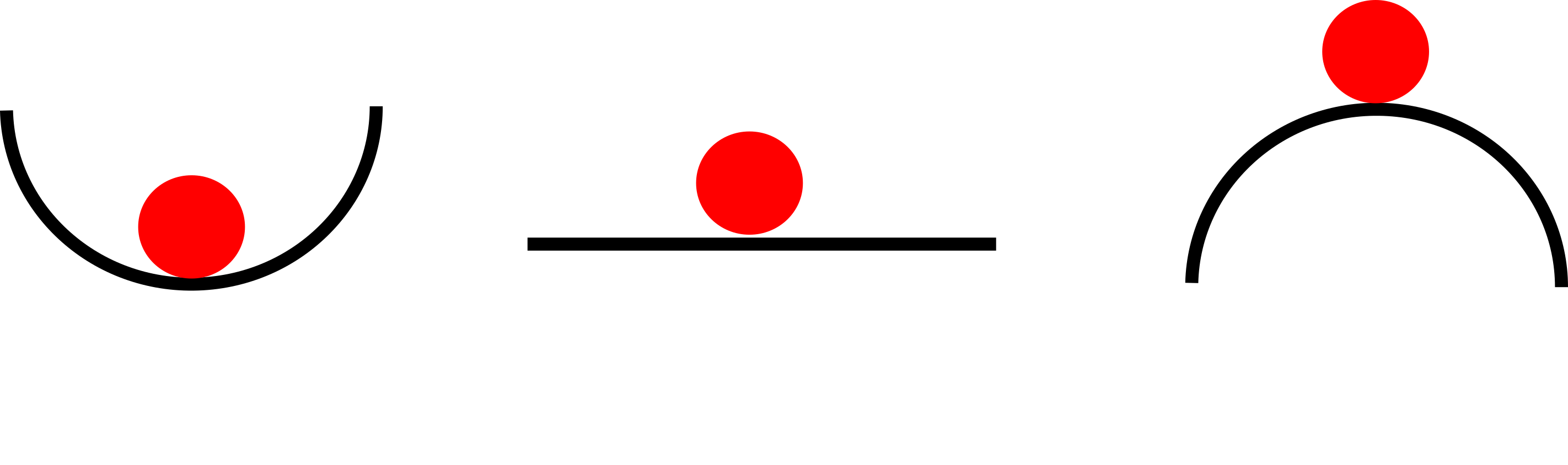

This is best described with a graphic:

Fig. 28 Stable, Neutral, and Unstable#

In Figure Fig. 28 a ball is placed on three surfaces in an equilibrium state. On the leftmost case, if disturbed (pushed left or right), the ball would return to its initial equilibrium condition. This is statically stable. In the centre case, after a disturbance the ball would find a new equilibrium condition - this is statically neutral. On the rightmost case, the ball would accelerate away from the initial condition - this is statically unstable.

For the simple ball case, with no forcing or excitation, it can be appreciated that the actual end position of the ball is dictated by its static stability. That is, there are no dynamic phenomena that cause the behaviour to change with time. By contrast, this is not the same for an aircraft - that is, an aircraft may have static stability, but have longer-term trend to move away from equilibrium. This is dynamic stability.

Dynamic stability#

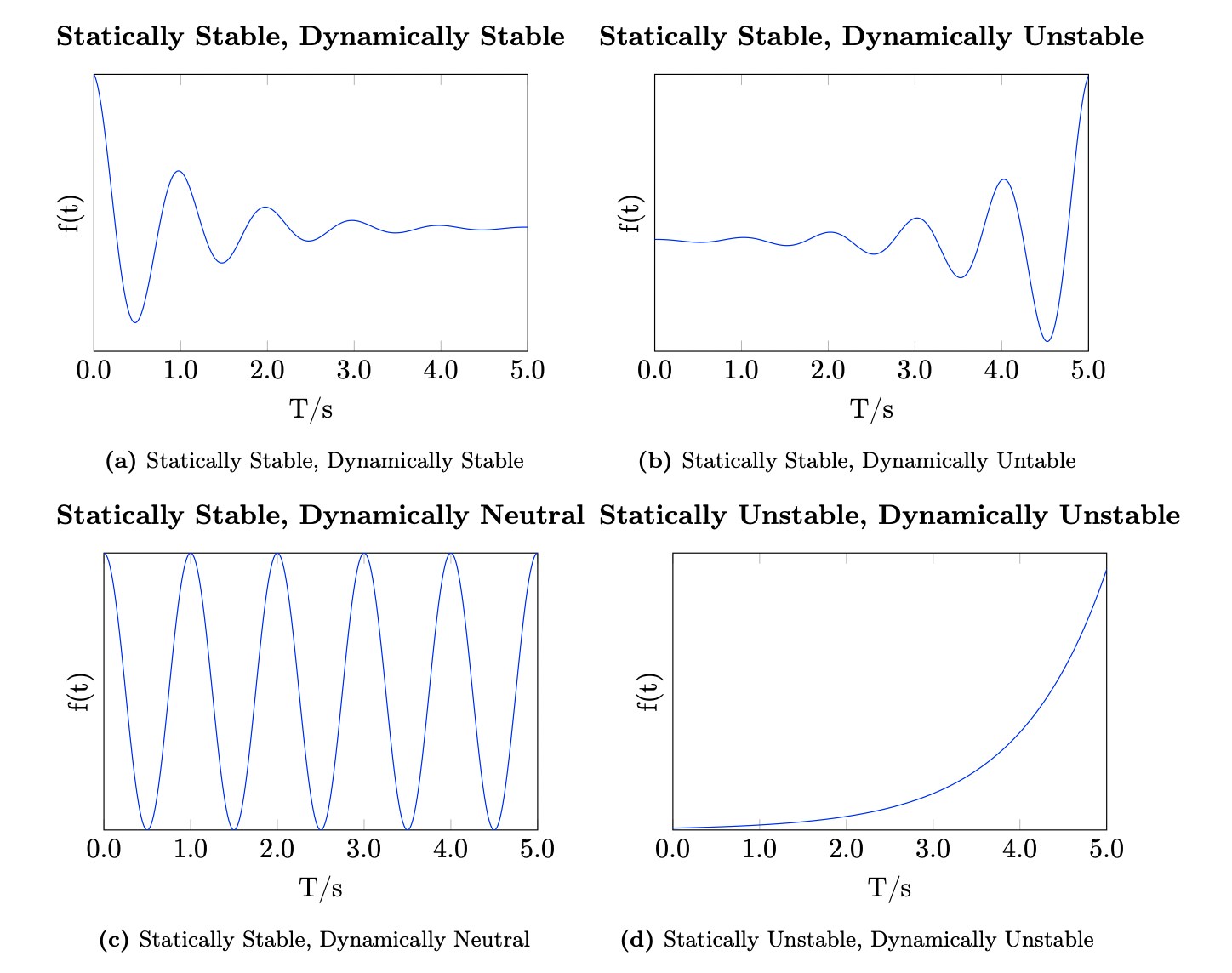

Dynamic Stability describes whether or not the aircraft will actually return to its trim state following a disturbance. An aircraft may be statically stable, but dynamically unstable. Static instability, however, is always accompanied by dynamic instability. See Figure Fig. 29 for examples of the combinations of static/dynamic stability as a response to a disturbance at \(t=0\). In Figure Fig. 29, \(f(t)\) is any function describing an aircraft state; these are the aircraft velocities and angular orientations.

Fig. 29 Different Stabilities#

Stability Requirements#

It can be appreciated that in certain situations, good stability is highly desirable - it will be shown that for any aircraft certified under FAR 23, pitch stability is a necessary requirement to be able to produce an aircraft.

However, too much stability can make an aircraft sluggish. Stability is a measure not simply of how well an aircraft responds to disturbances - it also denotes how difficult the aircraft will be to manoeuvre. For this reason, the same stability characteristics are not found in airliners and fighter aircraft.

To explore the dynamic stability of an aircraft requires the full equation of motion, which are nine coupled nonlinear equations. Modules 3, 4, and 5 of this course will be spend deriving, linearising, and then utilising these equations.

Before them, however, we can gain a good intuitive sense of static stability by using some reduced models. With these reduced models, some great predictions can be made about the following:

What size does my tail need to be?

What tail incidence gives zero elevator deflection at cruise \(C_L\) (and thus the lowest drag in cruise)?

How far forward can I place cargo in an aircraft?