Assumed knowledge#

This course assumes a certain level of knowledge on the reader and will not be formally taught in class - you will have been taught this at earlier levels in your undergraduate studies but:

Students forget things

Repetition helps to reinforce learning

So a review of what is assumed of your knowledge is suitable at this juncture.

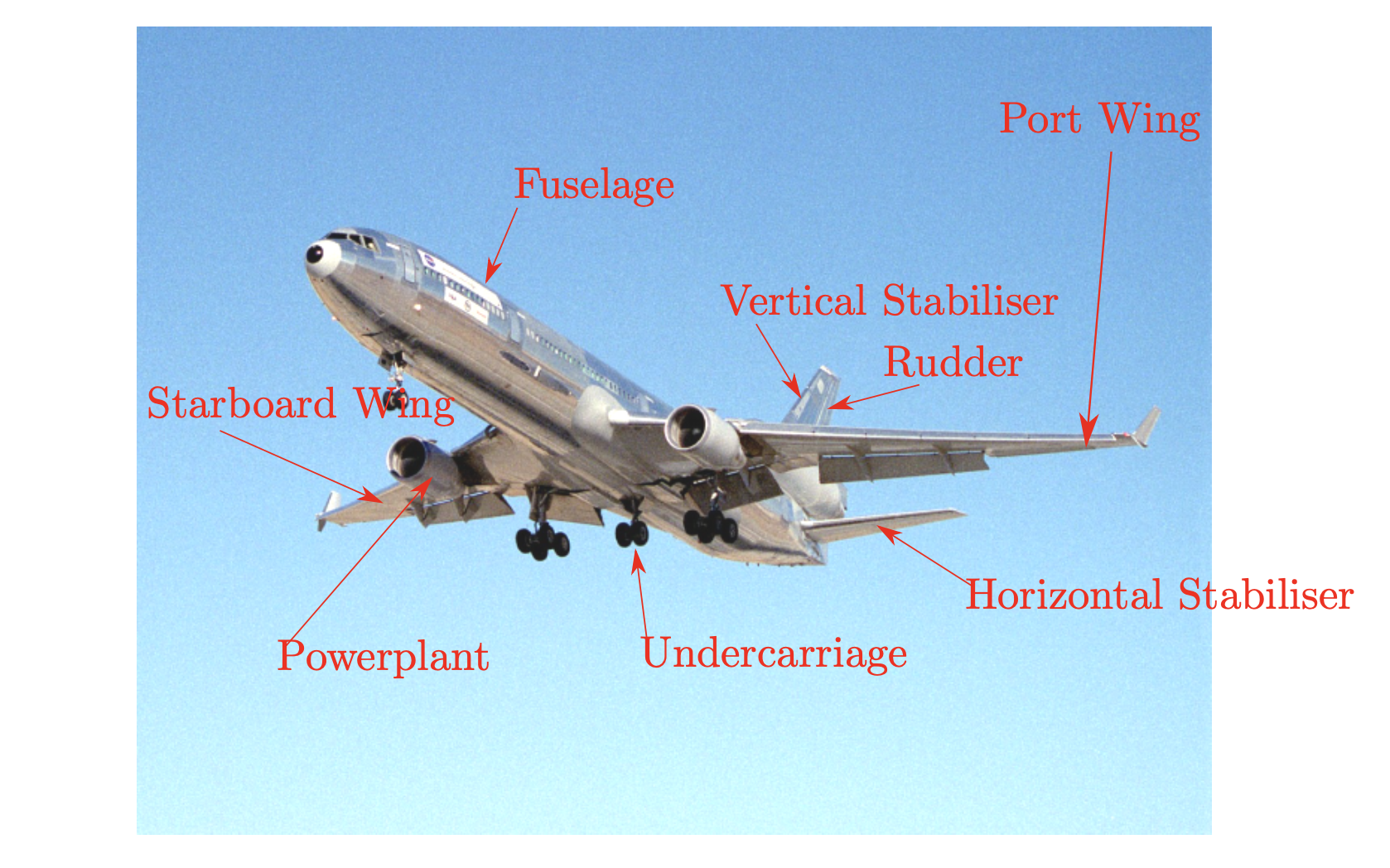

Aircraft Anatomy#

The basic parts of a standard fixed-wing aircraft are labelled in Fig. 3. Flight is controlled through movable parts of the aircraft, and from adjusting the propulsion.

Fig. 3 Major Aircraft Components#

Aircraft have control surfaces in red and high-lift devices in blue in Fig. 4. Note that some aircraft have additional flow control devices such as spoilers but there are not discussed here.

Fig. 4 Aircraft Control Surfaces and High Lift Devices#

The control surfaces are there to alter the aircraft’s attitude (its orientation in 3D space). They are:

Ailerons - these are outboard on each wing, and operate in differential mode, meaning if one goes up, the other goes down. These are effected via a sideways stick/yoke movement. This increases lift on one wing, and decreases it on the other, effecting a roll rate, \(p\), which changes the roll angle, \(\phi\).

The elevator is usually situated on the horizontal stabiliser, and both sides move together. This increases/decreases the tail lift, and changes the aircraft pitch attitude, \(\theta\). This is controlled by moving the stick/yoke forward/aft.

The rudder is on the vertical tail, and is a single control surface. If the rudder moves to the port (left), it creates a sideways aerodynamic force on the tail towards starboard (right), which moves the aircraft nose-port to a sideslip angle, \(\beta\). This is controlled using pedals in the cockpit.

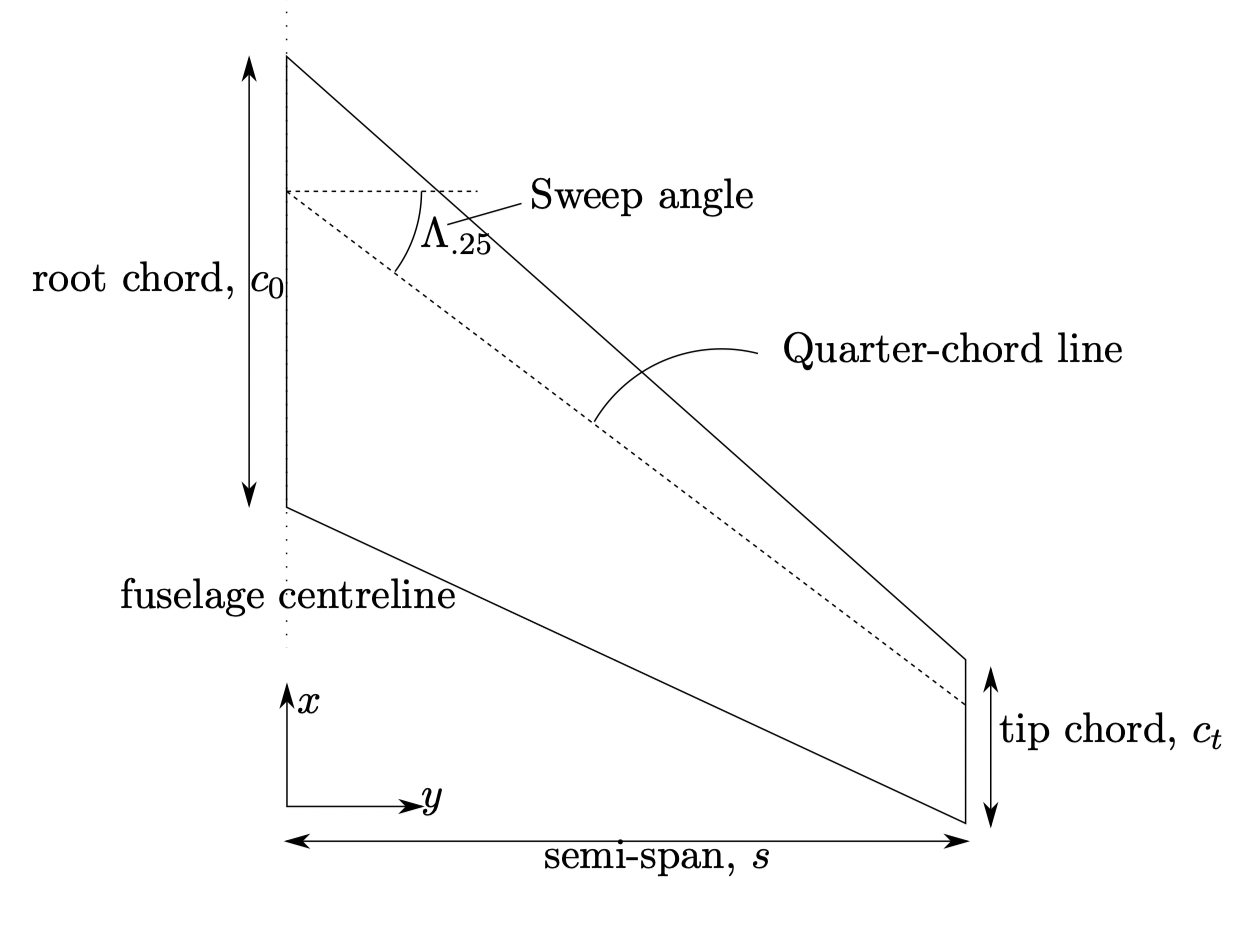

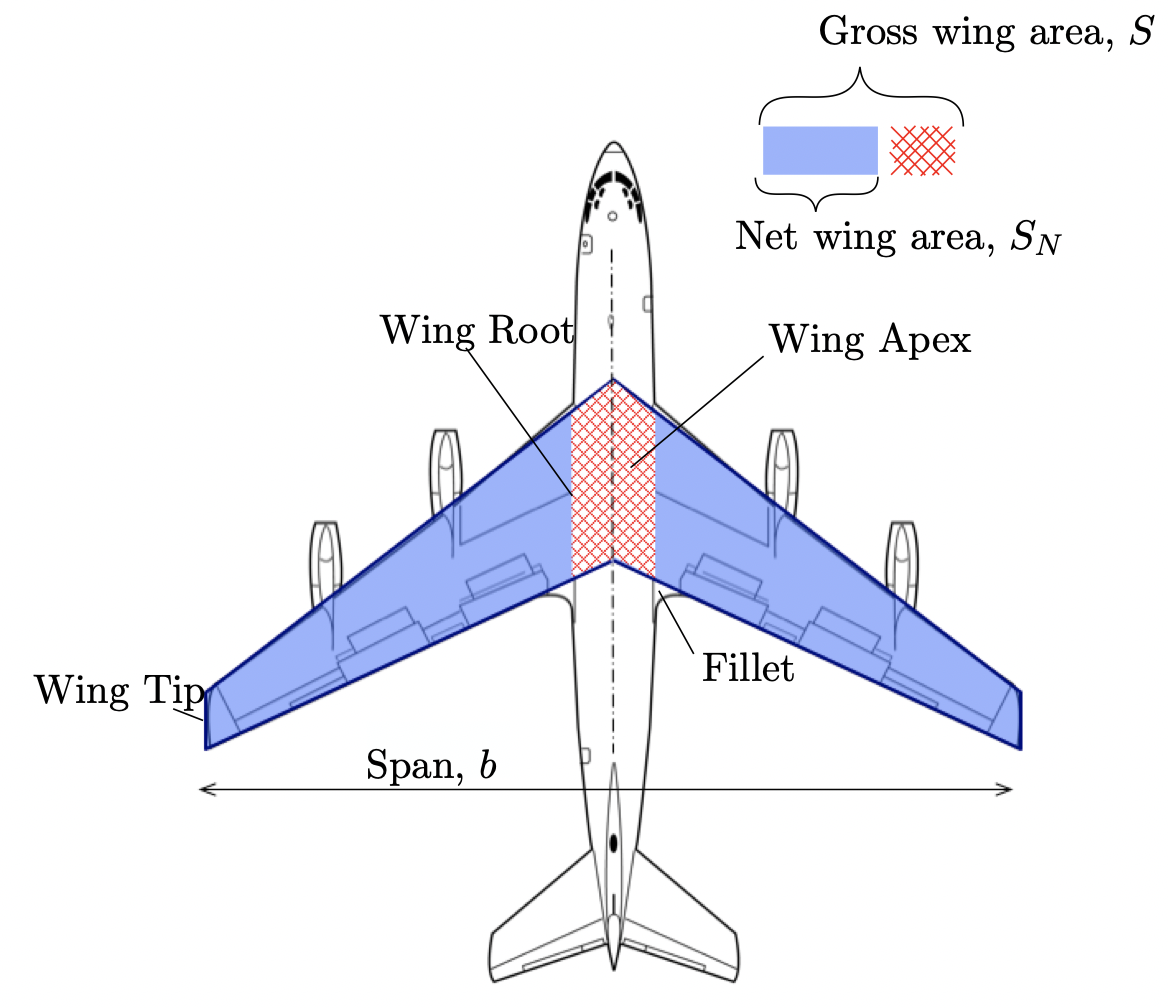

We will look at trapezoidal wings for most of this course - see Fig. 5. In general, we usually define wing parameters in terms of gross wing - see , \(S\). We represent the wing with a simple trapezoid:

Fig. 5 Aircraft Trapezoidal Wing#

Fig. 6 Aircraft Wing Areas#

you will note that the swing, sweep, which is a measure of how far back the tip is compared to the root, is measured by the sweep of the quarter-chord line. The chord is the length of the wing in the direction of travel (hence vertical in the image). The so-called root chord is usually defined on the aircraft centerline, and not at the actual aircraft root.

Wing parameters#

We can define a few parameters:

Aerodynamic, Propulsive, and Inertial Forces#

As will be covered in the Aircraft Performance module, the simplest regime of flight is that of steady, level flight. Steady means not accelerating, and level means that there is no variation in altitude - this does not mean that the wings are level, so the aircraft may be turning in a steady turn.

Whilst this will be covered in detail later, the basics of this regime should be familiar from previous courses.

Since the aircraft is not accelerating, the forces must be in equilibrium. We summarise our forces on the aircraft as two aerodynamic forces, one propulsive, and one inertial:

Lift - \(L\) - the aerodynamic force normal to the incident flow velocity, acting in a ‘lifting’ sense.

Drag - \(D\) - the aerodynamic force parallel to the incident flow velocity, opposing motion.

Weight - \(W\) - the inertial force acting downward; \(W=m\,g\) where \(g=9.80665\text{m}\,\text{s}^{-2}\), the acceleration due to gravity.

Thrust - \(T\) - the propulsive force parallel to the aircraft longitudinal axis, providing motion.

Fig. 7 Equilibrium Forces#

Aerodynamic Coefficients#

In general, it’s useful to be able to remove units from expressions in engineering for a number of reasons:

It enables us to work between unit systems (i.e., between metric and imperial unit systems) without conversion.

It enables us to compare aircraft of differing sizes in terms of performance.

It enables us to perform scale model work of aircraft and extend the results to full-size.

Hence, as presented in the preceding section forces \(L\) and \(D\) represent dimensional lift and drag, which we may measure in Newtons, Pounds-Force, Dyne, or Kip.

Note

You may not have heard of the last two. Don’t worry - we won’t be using them.

To remove the dimensions from these forces, we divide by something else with the same dimensions. You should be comfortable with the fact that the lift is proportional to the ‘dynamic pressure’, \(q_\infty\)

where \(\rho\) is the fluid density, and \(V\) is the velocity of the fluid. Dynamic pressure has dimensions of:

We know that lift and drag may be represented in Newtons, which have units of \({\text{N}}={\text{kg}\,\text{m}\,\text{s}^{-2}}\) which has dimensions of

to get something that has the same dimensions as the aerodynamic forces, we need to multiply the dynamic pressure by some area. The area that we choose is the wing area, \(S\), which we’ll define in more detail later. But now we’ve reached the definition of the three-dimensional lift and drag coefficients:

The uppercase \(L\) and \(D\) in the subscript means that we’re looking at the three-dimensional lift and drag coefficients. As aeronautical engineers we often like to look at an infinitesimal slice of a wing, which we call an aerofoil/airfoil.

Note

Though I live and work in America, I’m a Brit. Hence the ‘u’s and ‘s’ in place of ‘z’s. Aerofoil is British English, Airfoil is US English.

If we wish to have the lift and drag quantified on 2D aerofoil, then we look at the lift and drag per unit span, which we denote with a lowercase \(l\) and \(d\). The corresponding two-dimensional lift and drag coefficients are:

where we’ve now introduced a new parameter, \(c\), in place of the wing area. This \(c\) represents the chord of the aerofoil, which is simply the length from the very front (the leading edge) to the very aft (the trailing edge).

Aerofoils and Lift#

As discussed above, an aerofoil is an infinitesimal section of a wing, which we can represent in two dimensions (this is helpful, as drawing in 3d is difficult!). The simplest aerofoil is a symmetric one.

Note

The simplest aerofoil with thickness - as the simplest ‘foil’ could be argued to be a flat plate.

The nondimensional longitudinal axis is the \(x\) direction, and the distance from the front (leading edge) to the tail (trailing edge) of the airfoil is the chord line.

The simplest ‘standard’ airfoils are the NACA 4-digit series. Where the four digits are numbers. The format is \(MPXX\) where:

\(M\) is the maximum camber expressed as a percentage of the chord. In the example \(M\)=2 so the camber is 0.02 or 2% of the chord.

\(P\) is the position (in the \(x\) direction) of the maximum camber expressed in tenths of the chord length. In the example P=4 so the maximum camber is at 0.4 or 40% of the chord.

\(XX\) is the thickness as a percentage. In the example \(XX\)=12 so the thickness is 0.12 or 12% of the chord.

We have already discussed the chord line, and now also the camber line. For reasons that you should have discovered in your studies, a cambered aerofoil produces more lift and a symmetric one for the same angle of attack (before stall). The camber line is defined as the locus of points midway between the upper and lower surface. For a NACA 4-digit airfoil with nonzero first and second digit, you can immediately observe that the aerofoil will have camber. The camber line is the midpoint between the upper and lower surface at all points.

You should be comfortable with NACA 4 and 5 digit series aerofoils - these are defined by polynominal functions representing the camber line and the thickness distribution. A code snippet below enables you to plot the NACA 4-digit series. Click the rocket and choose ‘launch thebe’ or open this page in Binder to change the aerofoil section.

Show code cell content

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

plt.close('all')

def naca4(number='0012', n=1000):

"""

Plots the aerofoil for the given 4 digit NACA number string

"""

m = float(number[0])/100.0

p = float(number[1])/10.0

t = float(number[2:])/100.0

a0 = +0.2969

a1 = -0.1260

a2 = -0.3516

a3 = +0.2843

a4 = -0.1015

# Make a vector of the x spacing

x = np.linspace(0, 1, n)

# Get the thickness distribution

yt = 5 * t * (a0*x**.5 + a1*x + a2*x**2 + a3*x**3 + a4*x**4)

# Get the camber line

yc = np.zeros(x.shape)

if p > 0:

yc[x <= p] = m / p**2 * (2 * p * x[x <= p] - x[x <= p] **2)

yc[x > p] = m / (1 - p)**2 * ((1 - 2 * p) + 2 * p * x[x > p] - x[x > p]**2)

# Get the gradient of the lines

dyc_dx = np.zeros(x.shape)

if p > 0:

dyc_dx[x <= p] = 2 * m / p**2 * (p-x[x <= p])

dyc_dx[x > p] = 2 * m / (1-p)**2 * (p-x[x > p])

theta = np.arctan(dyc_dx)

# Get the upper and lower surfaces

yu = yc + yt * np.cos(theta)

yl = yc - yt * np.cos(theta)

xu = x - yt * np.sin(theta)

xl = x + yt * np.sin(theta)

# Put into Selig format

# Y = np.concatenate((yu[::-1], yl))

# X = np.concatenate((x[::-1], x))

plt.figure()

plt.plot(xu, yu, label="Upper Surface")

plt.plot(xl, yl, label="Lower Surface")

plt.plot(x, yc, label="Camber Line")

plt.plot([x[0], x[-1]], [yc[0], yc[-1]], '--', label='Chord Line')

plt.legend()

plt.gca().set_aspect('equal')

# plt.gca().axis('off')

plt.title(f"Normalised aerofoil for NACA {number}")

plt.gca().legend(bbox_to_anchor=(1.1, 1.05))

return

%matplotlib notebook

naca4('2406')

The most important parameter for lift is angle of attack. We define the incident velocity at \(V_\infty\), and the angle of attack is the angle it makes with the chord line of the aerofoil. This angle is given the symbol \(\alpha\) - see Fig. 8.

Fig. 8 Aerofoil Angle of Attack#

Where does lift come from?#

Fundamentally, an aerofoil provides a pressure difference by accelerating the flow over the upper surface, and retarding the flow over the lower surface. This has nothing to do with the airflow ‘catching up’ at the trailing edge - and though you’ll find plenty of sources for the so-called Bernoulli fallacy, it is wholly incorrect.

In your third year classes, you will have covered the circulatory theory of lift, and discovered that it is the tendency of the aerofoil to ‘circulate’ the air that provides lift. Hence a symmetric aerofoil at an angle of attack produces lift, and a cambered aerofoil produces some lift at zero angle of attack.

If you want to describe where lift comes from, you can say that ‘an aerofoil with a sharp trailing edge, if immersed in a viscous flowfield, will create about itself sufficient circulation such that the flow leaves the trailing edge smoothly (aka the Kutta condition).

The key effects of this are:

The flow is accelerated over the upper surface and retarded over the lower surface

This causes a pressure rise on the lower surface and a pressure drop on the upper surface

These pressures, when integrated, give rise to lift (and some drag, which we’ll talk about later).

The lift coefficient is linearly proportional to the angle of attack.

Lift vs Alpha (and a few other things).#

If we plot the lift coefficient vs angle of attack, we get a curve that looks like Fig. 9. You will notice:

The first part of the curve is linear, and it has the slope of \(C_L=2\,\pi/\text{rad}\).

The lift curve slope is defined as \(a=\frac{\partial C_L}{\partial\alpha}\), which we define just for this linear part.

The curve stops being linear as it approaches its maximum - this is the start of nonlinearity.

The maximum lift the aerofoil can produce is \(C_{Lmax}\).

At angles of attack beyond \(\alpha_{stall}\), the aerofoil is fully stalled and the flow is separated

It should be \(C_l\) and not \(C_L\) on the y-axis, but I am too lazy to correct it.

For the symmetric aerofoil, we can determine the lift from \(C_L=a\,\alpha\), where \(a\) is the lift curve slope. When we introduce camber to the aerofoil, we shift the \(C_L-\alpha\) curve to the left. You’ll note that for the symmetric aerofoil, there is zero lift produced at an angle of attack of zero. The cambered aerofoil produces \(C_{L0}\) at \(\alpha=0\), and we note that there is some negative angle of attack at which it produces zero lift, which we call \(\alpha_0\). Fig. 10:

The lift curve slope of a cambered aerofoil will be the same, so the lift of a cambered aerofoil can be determined from \(C_L=a\left[\alpha-\alpha_0\right]\).

Fig. 9 Lift Coefficient vs Angle of Attack - Symmetric Aerofoil#

Fig. 10 Lift Coefficient vs Angle of Attack - Cambered Aerofoil#

In general, we can use \(C_L\) to compare aerodynamic performance, and we note that \(C_L\) is simply a function of the angle of attack. However, \(C_L\) is also a function of two important parameters that we’ll mention here:

Compressibility#

The fastest that information can travel through a fluid is the speed of sound, \(a=\sqrt{\gamma\,R\,T}\) where the speed of sound at sea-level is around 340. Because the aerofoil disturbs the flow around it, these disturbances move at the speed of sound.

As the fluid velocity gets faster, these disturbances travel at rates that are slower and slower compared to the fluid velocity. Whilst we won’t get into the mathematics of compressible flow, we can probably see that the lift produced will be a function of how fast the fluid is traveling compared to the speed of sound. So we have just defined the Mach number, which is our dimensionless measure of speed compared to \(a\):

Viscosity#

How ‘sticky’ the air is affects how well it adheres to the aerofoil, and hence when stall will occur. It also affects how much drag is produced. Aerodynamicists use another dimensionless parameter, Reynold’s number, which is the ratio of the inertial forces to the viscous forces in a fluid.

Where \(\rho\) and \(V\) are as they were before, and \(l\) is the ‘characteristic length’. If we’re looking at aerofoils, it will be the chord length. For other problems, it might be the length of the whole aircraft. \(\mu\) is the dynamic viscosity which has units of . Check that this is dimensionless using the same technique as we did for the lift coefficient.

Lift Summary#

Lift is the aerodynamic force arising from a pressure differential due to the flow being accelerated over the top of a lifting surface, and retarded over the bottom.

For our purposes, lift is associated with the creation of ‘circulation’ which is the tendency of the flow to circulate the aerofoil in a manner which causes this flow change.

Note

Lift can be produced in supersonic flow, and in impulsive flow without circulation, but these are graduate-level topics.

The lift coefficient is primarily a function of angle of attack, and this relationship is linear until stall.

The lift coefficient is also a function of Mach number and Reynold’s number, so care must be taken when comparing data from dissimilar flow regimes.

Drag#

Drag the component of aerodynamic force that opposes aircraft motion. Whilst it might appear slightly more easy to intuit than lift, it can be a whole load more complicated. Semenal textbooks are written on Drag, so the following is presented as a simplification to be able to use drag to develop relationships for aircraft flight mechanics. We’ll firstly describe two main sources of drag:

Skin Friction Drag#

Skin friction drag is a direct result of viscosity. We discussed the concept of a boundary layer in class, and we know that the flow directly next to the surface of a solid body is stagnant - this is why dust doesn’t get removed from your moving car!

Fundamentally, we can consider the fluid velocity closest to the surface as zero, and it increasing with the distance from the surface until it reaches the freestream velocity. In order for the flow to be retarded, work needs to be done to it, and this is transferred through shear forces in the fluid and frictional forces between the fluid and solid body. This force is applied to the body in the same direction is fluid motion, and is called skin friction drag.

We note that for more complex geometries such as aerofoils, the local surface direction may not be the same as the streamwise direction, so the component of the force parallel to the inclement freestream must be calculated.

Pressure Drag#

We have already established that lift is caused by a pressure difference on an aerofoil being resolved into the direction normal to the fluid motion. If we resolve these pressures into a direction parallel to the freestream, we arrive at pressure drag. We further subdivide pressure drag into:

Pressure Drag 1: Form Drag#

Associated with the growth of a boundary layer. We can appreciate that the boundary layer, and a trailed wake will change the effective size of a body that a fluid must move around. Hence a large boundary layer will cause more drag. If we recall our ideal cylinder in 2D flow, we’ll note that it has zero drag (no wake, no pressure drag, no friction):

As we introduce viscosity, we also introduce the Reynold’s number of the flow, and change the attachment and separation points. This gives us a wake of varying size, which depends on the Reynold’s number:

Fig. 11 Different Wakes Behind 2D Cylinder Dependent on Re: Borrowed from Heat Transfer by A. Mills#

Note that the size of the wake is not necessarily a linear or continuous function of the Reynold’s number between these two examples - but for these two examples, the form drag would be higher with the lower \(Re\) example.

Pressure Drag 2: Induced Drag#

A 3D effect associated with a trailing vortex system. A wing that produces lift will produce a tip vortex, causing the air to rotate behind the aircraft. The energy associated with imparting this rotational motion to the air is induced drag.

Pressure Drag 3: Wave Drag#

Associated with shocks. We don’t really need to cover it in this course

Of the components of drag above, we note that both skin friction and form drag are due to viscosity, and hence cannot be modelled in the potential/’ideal’ aerodynamic model we developed in class. We’ll lump these two together and call it profile drag, which is the combined drag due to viscous effects.

To reduce form drag, we want a ‘nice’ separation (a laminar one). This has been known since at least 1810 when Sir George Cayley produced his minimum drag shape (which it has been suggested was modelled on a Trout!):

Fig. 12 Sir George Cayley’s Minimum Drag Shape#

We can see a similarity with a basic aerofoil shape:

Rapid change in thickness at the leading edge.

Gentle change in thickness towards the trailing edge.

Sharp trailing edge.

These things help reduce form drag by having laminar separation, but in doing so we’ve increased the surface area of the body. Thus, we have increased skin friction drag. It follows that to minimise profile drag, we have a compromise between skin friction and form drag. We can see that a flat plate and cylinder of the same cross-sectional area have different total drag due to form drag - see:

Fig. 13 Skin Friction and Form Drag: Borrowed from Unknown Source#