Introduction#

The following definitions will be revision, but a thorough understanding of them is imperative for the remainder of this course.

Newton’s laws of motion#

In this course we utilise Newtonian Mechanics - Newton’s laws should be familiar, and you should be able to recite them:

An object remains at rest or in a state of uniform motion unless acted on by an external, unbalanced force.

Net force acting on rigid body is equal to its absolute momentum flux, or \(\sum\vec{F}=m\cdot a_{abs}\).

Every action force has a reaction force that is equal in magnitude, and opposite in direction.

Newton’s second law will be used in this section to derive the full six degree of freedom (6DoF) equations of motion for unconstrained aircraft flight. Before diving into the derivation, further definitions are required:

Most of the quantities used are easiest to define in different axes systems

A thorough understanding of relative motion will need to be employed

Reference Frames and Aircraft Axis Systems#

All motion is relative - there is no luminiferous aether[1], and there is no universal ‘grid system’ in which we can define position or motion. In the absence of this, we define different axes systems depending on what helps to simplify the mathematics that we need to use - it is easier to define forces in an axis system where those forces are aligned with the reference system.

Newton’s laws are only valid in an inertial reference frame - one that is not moving. We use the Earth as our inertial reference frame - this is not actually the case as it is obviously moving, but for flight mechanics purposes, we rely on the fact that the rotation of the Earth is slow compared to aircraft motions.

A note on vector notation#

To differentiate vector quantities from scalar quantities, several conventions are commonplace. If \(U, V, W\) are vector components, the vector may be defined using

Boldface \(\displaystyle\mathbf{U}=[U,V,W]^T\)

Arrow \(\vec{U}=[U,V,W]^T\)

Underline \(\underline{U}=[U,V,W]^T\)

I tend to use \(\vec{U}\) in typeset documents as it causes the least conflicts when using LaTeX. When writing on the board, I tend to use \(\underline{U}\) notation as it is easier - but sometimes I’ll draw an arrow if I’m feeling adventurous[3]. I don’t mind which you use, as long as you are consistent within a single derivation. Just be aware that things change between sources.

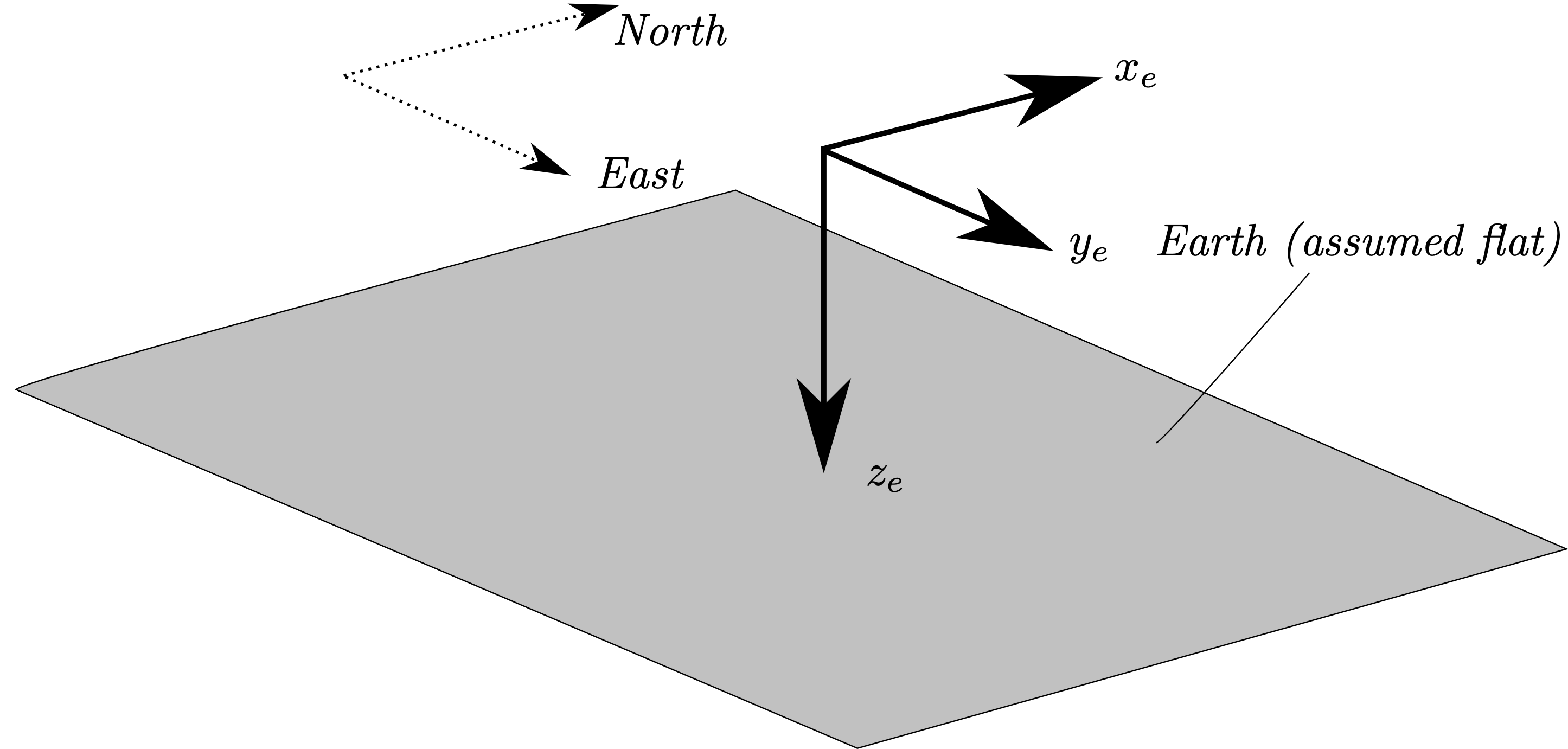

Earth Axes#

We utilise the Earth axis system, see Figure , because, for our purposes, it is an inertial reference frame - so we require this in order to utilise Newton’s second law. We make some simplifications, and impose the following:

Assume the Earth is a flat plane [4]

NED (North, East Down) = \(x_E, x_E, x_E\)

Fig. 39 Earth Axes#

Aircraft Body Axes#

We also require a frame of reference that is fixed to the aircraft because:

That is the frame of reference in which the pilot sits, so we require one to determine forces on them

Moments/products inertia, and centre of gravity position are easily defined in an axis system fixed to the aircraft

This axis system is usually defined with its origin at the aircraft centre of gravity.\

\(x\) is defined positive forward, and may be defined along the propeller rotation axis for a single-engine propeller-driven aircraft, along the floor for a large transport aircraft, or along the wing root chord line.

\(y\) is defined along the starboard axis along a plane equidistant vertically from both wings at each spanwise location (\(Y_B\) does not not travel along a wing dihedral angle).

\(z\) is defined down, normal to the plane defined by the \(x\), \(y\) intersection.

These have already been introduced in the previous module.

We can normally define thrust in aircraft body axes, and we may also define aerodynamic forces in body axes (as normal and axial force), but it is more convenient to define aerodynamic in stability axes as lift and drag.

Stability Axes#

Warning

Note that the nomenclature of wind/stability systems is inconsistent depending on which textbook you look at. The version presented herein is the most common, and the most sensible

Aircraft, in general, are usually flown at some angle of attack, \(\alpha\) - which means that the incident freestream velocity is not aligned with the aircraft body axes. Lift and drag are defined parallel to, and normal to the incident flow vector, so we require an axes set called stability axes - \([x_s, y_s, z_s]\).

We rotate the aircraft body axes through \(\alpha\), around \(y\) - thus \(y=y_s\).

The \(x/y\) planes of body and stability axes intersect along the shared \(y, y_s\) axis - [fig:stabilityplanes]{reference-type=”ref” reference=”fig:stabilityplanes”}.

The \(x/z\) planes of body are co-planar, but rotated about \(\alpha\) - [fig:stabilityplanesXZ]{reference-type=”ref” reference=”fig:stabilityplanesXZ”}.

It is important to note that this treatment neglects sideslip \(\beta\) - so we are treating \(V_\infty\) as the projection of the relative wind into the aircraft body \(x_b/z_b\) plane.

Aircraft data is usually defined in the stability axes system - it is important, however, to have an appreciation of wind axes.

<>:178: SyntaxWarning: invalid escape sequence '\c'

<>:178: SyntaxWarning: invalid escape sequence '\c'

/var/folders/4w/4bcfp26j6_1gn39czlk991z80000gn/T/ipykernel_85561/1281994850.py:178: SyntaxWarning: invalid escape sequence '\c'

mode='lines', name='$V_f\cos\\beta$',

Wind Axes#

Stability axes are defined from the projection of freestream into the \(X_b/Z_b\) plane. That is, disregarding sideslip.

Wind axes take account of this, and are aligned with \(x_w\) defined along the actual freestream.

In general, however, aircraft coefficients will be defined in stability axes - but you should have an appreciation of this axis set.

Defining quantities in different axes sets#

The axes systems that used in this course have been described - as mentioned earlier, it is easier to define certain quantities in one axis system over another:

Gravitational Force - Weight#

The aircraft weight vector is, by definition, aligned with the Earth Z (\(z_e\)) axis as it is oriented towards the centre of the Earth. That is:

Displacements#

For positioning purposes, the aircraft location must be defined in earth axes.

Propulsive Forces#

Aircraft thrust is generally aligned along the aircraft \(x\)-axis \(x\), and is thus best defined in body axes:

For this course we will disregard effects such as thrust axis misalignment or thrust vectoring, so this simplifies to

Aerodynamic Force#

The aerodynamic forces of lift, \(L\), and drag, \(D\), are, by definition, defined normal to and parallel to the incident flow vector, \(V_\infty^\prime=V_\infty\cos\beta\). It is most useful to use these force in stability axes:

Where the term \(F_{A_y}\) is the side component of aerodynamic force due to sideslip.

Translations and Rotations#

Aircraft velocity and accelerations are defined in body axes:

One must be careful with the equation above; in the case of zero angular motion, you may differentiate the absolute velocities \([U,V,W]\) to obtain the absolute acceleration \([a_x,a_y,a_z]_{abs}\), but for the case of non-zero angular velocity, these are not equivalent, \(a_x\neq\dot{U}\). This will all make a lot more sense (hopefully) when you’re introduced to Coriolis theorem later, but the fact that we cannot get absolute accelerations so simply deserves a mention at this juncture.

Angular velocities of the aircraft, with respect to the inertial reference frame, are defined in body axes as roll, pitch, and yaw rates:

Note that if you see \(P\), \(Q\), or \(R\) in practice, they are defined as body angular rates, and are as measured in body axes.

Aircraft total forces and moments#

We define the total external forces and moments on the aircraft in body axes

The requirement for axis conversion#

Since it is desired to utilise Newtonian mechanics to define the motion of the aircraft, it is hence needed to be able to equate forces to the product of mass and accelerations (Newton’s second law).

So far, forces, displacements, and velocities are defined in all three axis systems - earth, body, and stability.

Relating stability and body axes is relatively simple since they are only rotated through a single angle, \(\alpha\). Body and earth, by contrast, are oriented at an arbitrary angular displacement to each other.

The aircraft attitude defines the relationship between earth and body axes, and this hence allows conversion of quantities between the two different axes systems.

To define the aircraft attitude, there are different ways that can be chosen from mathematics:

Sequence of Rotations

Quaternion methods

Direction cosine matrix

In this course, we will use the sequence of rotations - yaw, pitch, roll. These need to be defined in that order.[2]