Lateral Stability#

Lateral motions refer to the aircraft response in roll. In a static sense, there is no such concept as “roll stiffness” because there is no aerodynamic roll angle (the aircraft doesn’t know if the wind vector is rotated about its own axis).

“…the concept of roll stability, in the static sense, does not exist. At the most one could say that an airplane possesses neutral static stability in roll.”

—Aerodynamics, Aeronautics and Flight Mechanics, page 545

Some (mostly online, but that’s what you guys will find when searching) texts refer to the derivative \(C_{\ell_\beta}\) as roll stiffness, and I can see why, but it’s incorrect. This derivative is dihedral effect, and is an example of a cross-coupling, which will be talked about further in cross-couplings.

The second term is the roll damping - again, this is always restorative and hence negative.

Roll damping#

The parameter \(C_{\ell_{P}}\) or \(C_{\ell_\bar{p}}\) is known as roll damping, and refers to the rate of change of rolling moment with roll rate. Since both \(\ell\) and \(P\) are defined as a right-handed rotation, the stability condition for both of these is a negative derivative.

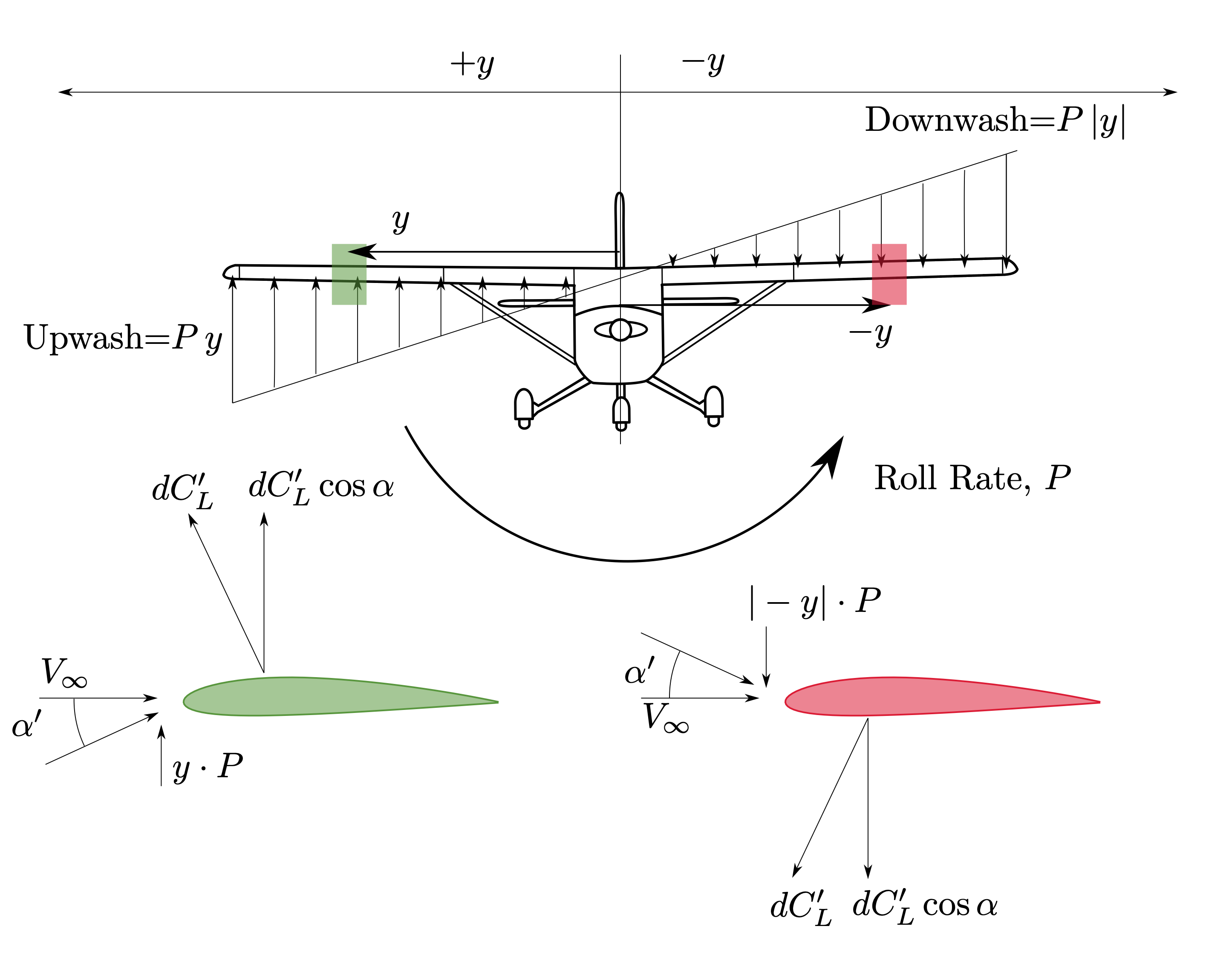

Roll damping is always restorative - consider a positive roll rate, \(P\), and the contribution due the aircraft wings:

Starboard wing down \(=\) upwash\(\,\therefore\alpha\uparrow\,\therefore C_L\uparrow\,\therefore C_\ell=f(y\cdot C_L)\downarrow\)

Port wing up \(=\) downwash\(\,\therefore\,\alpha\downarrow\,\therefore C_L\downarrow\,\therefore C_\ell=f(-y\cdot C_L)\downarrow\)

Hence an increase in roll rate \(P\) causes a decrease in rolling moment \(L\)

A negative roll rate similarly causes an increase in rolling moment

\(\therefore C_{\ell_P}<0\)

The contribution from the wings to roll damping is only part of the aerodynamic roll damping - similar contributions can be found from both the horizontal and vertical stabilisers, and a viscous component can be considered from the different surfaces including the fuselage.

The wing contribution is by far the largest, though, due to the greater moment arm that increases both the angle of attack change, and the moment produced by the lift increase/decrease.

Numerical Estimates#

An estimate can be considered of the roll damping based upon the wing contribution. In a simplified model of the aerodynamics, a strip model of the wing can be utilised. Consider a section of the wing at location \(y\), a wing element of span \(\text{d}y\)

Fig. 36 Upwash and Downwash on wings due to positive roll rate#

The vertical velocity, positive in the sense of an upwash is \(P\cdot y\).

The change in effective angle of attack, \(\alpha^\prime\), is therefore

Which, subject to the small angle approximation (expand the bit of code below if you’re interested about small angles) is

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import plotly.graph_objects as go

# What about the small angle assumption?

# We often use the small angle assumption in aerodynamics, but have you over looked at its validity?

# You also may not have seen the arctangent small angle assumption

angle = np.linspace(.1, 50, 1000)

rangle = np.radians(angle)

sin = np.sin(rangle)

cos = np.cos(rangle)

tan = np.tan(rangle)

sin_error = (rangle - sin)/sin*100

cos_error = (1 - cos)/cos*100

tan_error = (rangle - tan)/tan*100

fig = go.Figure()

fig.add_trace(go.Scatter(x=angle, y=sin_error,

mode='lines', name='$\\theta - \\sin\\theta$'))

fig.add_trace(go.Scatter(x=angle, y=cos_error,

mode='lines', name='$1-\\cos\\theta$'))

fig.add_trace(go.Scatter(x=angle, y=tan_error,

mode='lines', name='$\\theta-\\tan\\theta$'))

fig.update_layout(

title='Percentage error in small angle approximations', title_x=0.5,

xaxis_title="$\\frac{\\theta}{\circ}$",

yaxis_title="Percentage Error",

)

Show code cell output

<>:30: SyntaxWarning: invalid escape sequence '\c'

<>:30: SyntaxWarning: invalid escape sequence '\c'

/var/folders/4w/4bcfp26j6_1gn39czlk991z80000gn/T/ipykernel_85694/2465609629.py:30: SyntaxWarning: invalid escape sequence '\c'

xaxis_title="$\\frac{\\theta}{\circ}$",

The change in the lift produced at the wing element is

The change in the elemental lift, \(dL_{lift}\)

which gives a contribution to the rolling moment, \(dL\) recalling that \(L\) is positive starboard down, so the lift above produces a negative rolling moment

which is integrated from wingtip to wingtip to give the total rolling moment, \(L\), assuming a constant chord

The above expression is only valid for a rectangular wing, else the chord needs to be represented as a function of the span - this is covered well in McCormick’s textbook but is an exercise in algebra and calculus that we don’t need here.

From the definition of the rolling moment coefficient, noting that for a rectangular wing, \(S=b\,c\)

and hence the roll damping is

For a tapered wing, with \(\lambda=\frac{c_t}{c_0}\) (recall \(\lambda\) definition), McCormick gives:

Substitution of \(\lambda=1\) for the rectangular wing into the above confirms the result found.

It can be observed that for this estimate the roll damping derivative is proportional the main wing lift curve slope, and inversely proportional to the taper ratio. Since

you can further see that the roll damping is proportional to the wingspan, which makes sense due to the greater moment arm. You will also see that the roll damping is inversely proportional to the flightspeed which, again, makes sense - with a greater \(V_\infty\), the change in sectional angle of attack due to a given \(P\) is smaller.