Absolute Acceleration#

In deriving the equations of motion, we use Newton’s Second Law as the basis for equating force and the rate of change of both translational and angular momentum:

where \(a_{abs}\) is the absolute acceleration that defined in an inertial reference frame. Body axes velocities and displacements may be converted to absolute quantities via the Euler angle translation, but accelerations may not be treated as such, owing to the relative motion of the body axes with respect to the earth axes. Stated another way, the body accelerations are not absolute:

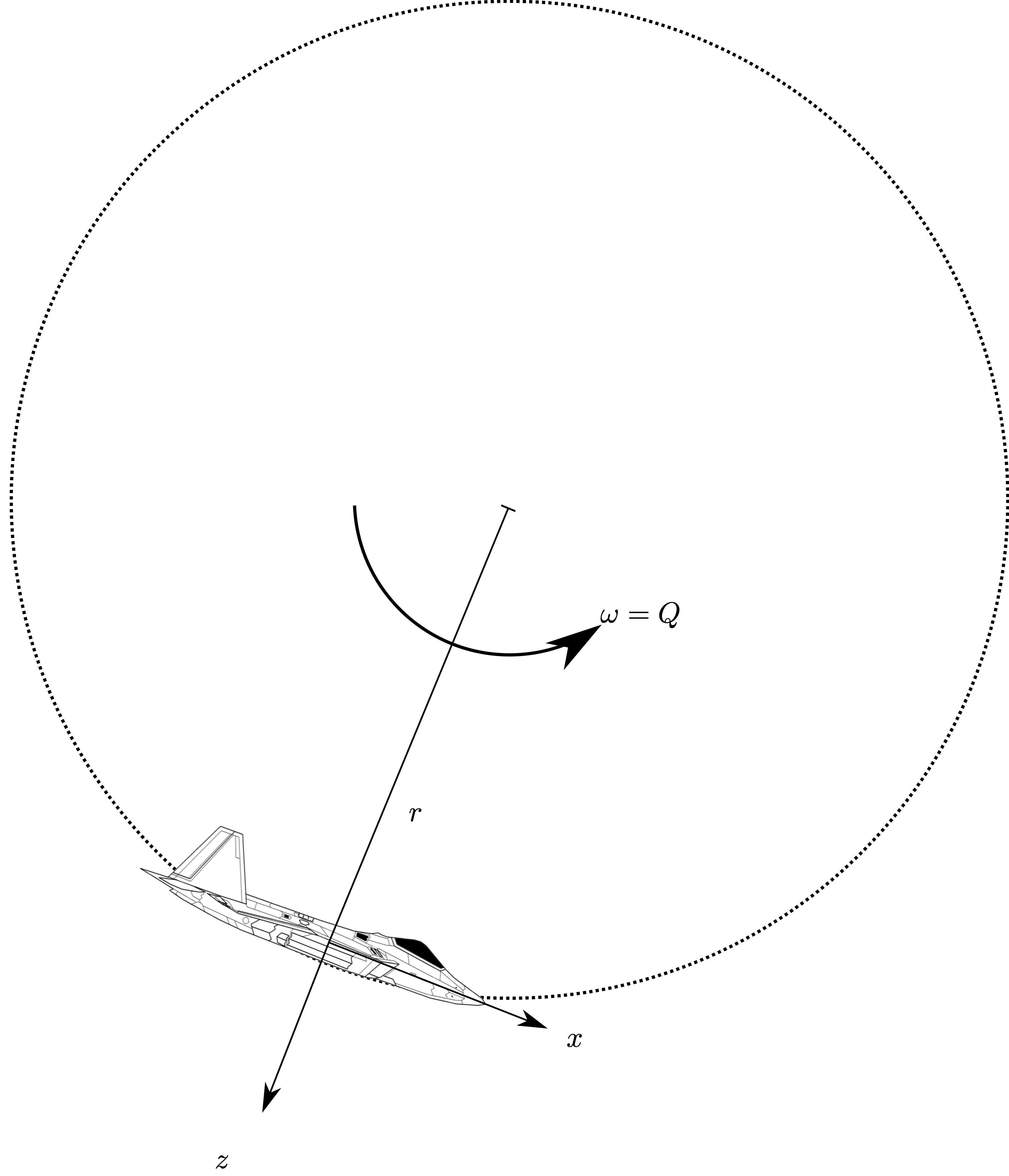

This may be demonstrated with a counterexample - an aircraft flying in a loop - see Figure Fig. 49.

Fig. 49 Aircraft flying in a loop#

From basic physics, we know that for steady motion in a circle of radius \(r\) with angular velocity \(\Omega\), the centripetal (centre seeking) acceleration is:

and that the tangential velocity, which in this case is equal to the aircraft \(u\) velocity i

which, if we substitute into our expression for centripetal acceleration and recognise that for this example, the angular rate \(\omega\) is equal to the body rotation rate around the \(y\) axis:

which gives us an apparent acceleration along the body \(z\) axis due to angular rotation, which is to be added to the local acceleration:

If we were to include terms because of all three body rates (you’d have to draw a similar example for a yaw rate - or wait until you’ve got the Coriolis identity), we would see that:

We can see that absolute acceleration is the sum of translational acceleration AND the vector product of angular and translational rates. Whenever we have rotation, we cannot simply treat absolute acceleration as the time derivative of velocities. In the following section, we’ll develop a methodology to treat this formally.

Relative Motion: General Form#

The extra terms arise because the aircraft axes are moving with respect to earth axes; body axes are a non inertial reference frame and (for our purposes) earth axes are. You are probably able to intuit some of these terms - such as the centrifugal force that is perceived in a rotating reference frame due to angular translation. We’ll develop a mathematical formulation to show the following

and

where (26) and (21) are the first and second order Coriolis identities. \(\ddagger\) is a vector quantity relating to translational motion. So, to yield absolute acceleration the absolute velocity can be used as \(\ddagger\) in (26) or the absolute position can be used in (21). \(()_{abs}\) refers to absolute quantities, which is what we need for Newton’s second law, whilst \(\left.\frac{\text{d}()}{\text{d}t}\right|_{Oxyz}\) refers to differentiation in a non-inertial reference frame.

Equations (26) and (21) tend just be given to the engineering student without a derivation, and I hate that sort of instruction since it doesn’t help learning or understanding, just parroting.

How will (26) and (21) be determined? Well we know that the effects are related to rotation of a non-inertial reference frame within an inertial one, and some rotation. So that looks like a good place to start.

General position and velocity vectors in unit vector form#

The general expressions for position and velocity are, as defined in a non-inertial reference frame (e.g., aircraft body axes)

The derivation can be performed using either. Taking Equation (22) and writing in unit vector form:

and the first derivative can then be written, using the product rule - noting that \(\dot{()}\) denote absolute derivative.

The terms \(\dot{x}, \dot{y}, \dot{z}\) are easy to intuit their meaning - these refer to any change in the vector in the non-inertial reference frame. The second set of terms \(\dot{\ii}, \dot{\jj}, \dot{\kk}\) are slightly less instructive. These refer to an apparent derivative that arises due to angular motion; if the original vector is \(\vec{r}\), then these are an apparent velocity. If the vector is \(\vec{V}\) then these are an apparent acceleration.

Since these are caused by angular rates \(\vec{\omega}=[P,Q,R]^T\), the effect of each of these rates can be explored on the unit vectors in time \(\Delta t\) - the limit of this change as \(\Delta t\rightarrow 0\) will give expressions for \(\dot{\ii}, \dot{\jj}, \dot{\kk}\).

Since \(P\), \(Q\), and \(R\) are all defined as rotations about body axes they can be explored independently as three Euler rotations - sequence is irrelevant here.

Warning

Why does sequence matter for \(\psi\), \(\theta\), \(\psi\), but not for \(P\), \(Q\), and \(R\)? The Euler angles \(\psi\), \(\theta\), \(\psi\) are defined in three different axes sets, earth, intermediate 1, and intermediate 2. None of these angles can be assumed small.

The body rates \(P\), \(Q\), and \(R\) are all defined in body axes and furthermore the angular distance covered in time \(\Delta t\) will be small.

If the unit vectors can be written as

then

and the total change to \(\vec{\boldsymbol{I}}\) is the sum of the changes due to the three angular rates

and all of the RHS components in (25) can be determined from Euler transforms. Consider each rotation as a movement from \(\vec{\boldsymbol{I}}\) to \(\vec{\boldsymbol{I}}^\prime\). The diagrams three Euler transforms are given below:

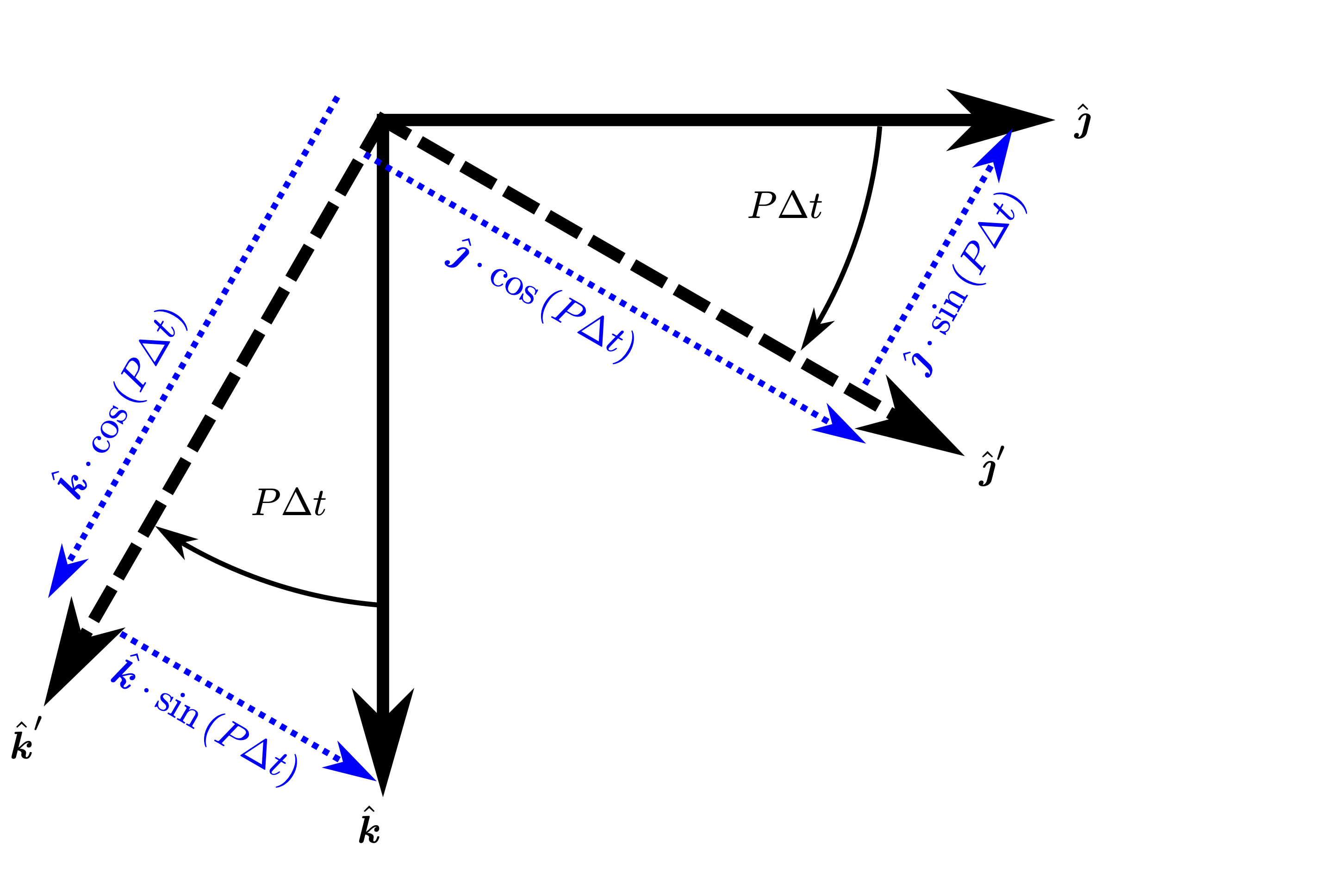

\(\Delta\vec{\boldsymbol{I}}_P\) - change to unit vectors due to body roll, \(P\)#

The angular displacement during time \(\Delta t\) due to body roll rate is \(P\Delta t\):

Fig. 50 Change to unit vectors due to roll rate \(P\)#

where

since ultimately the derivative will be given by looking at the limit as \(\displaystyle \lim_{\Delta t \to 0}\), the small angle assumption is justified

and thus we can define the \(\Delta\hat{\mathbf{I}}\) due to roll rate:

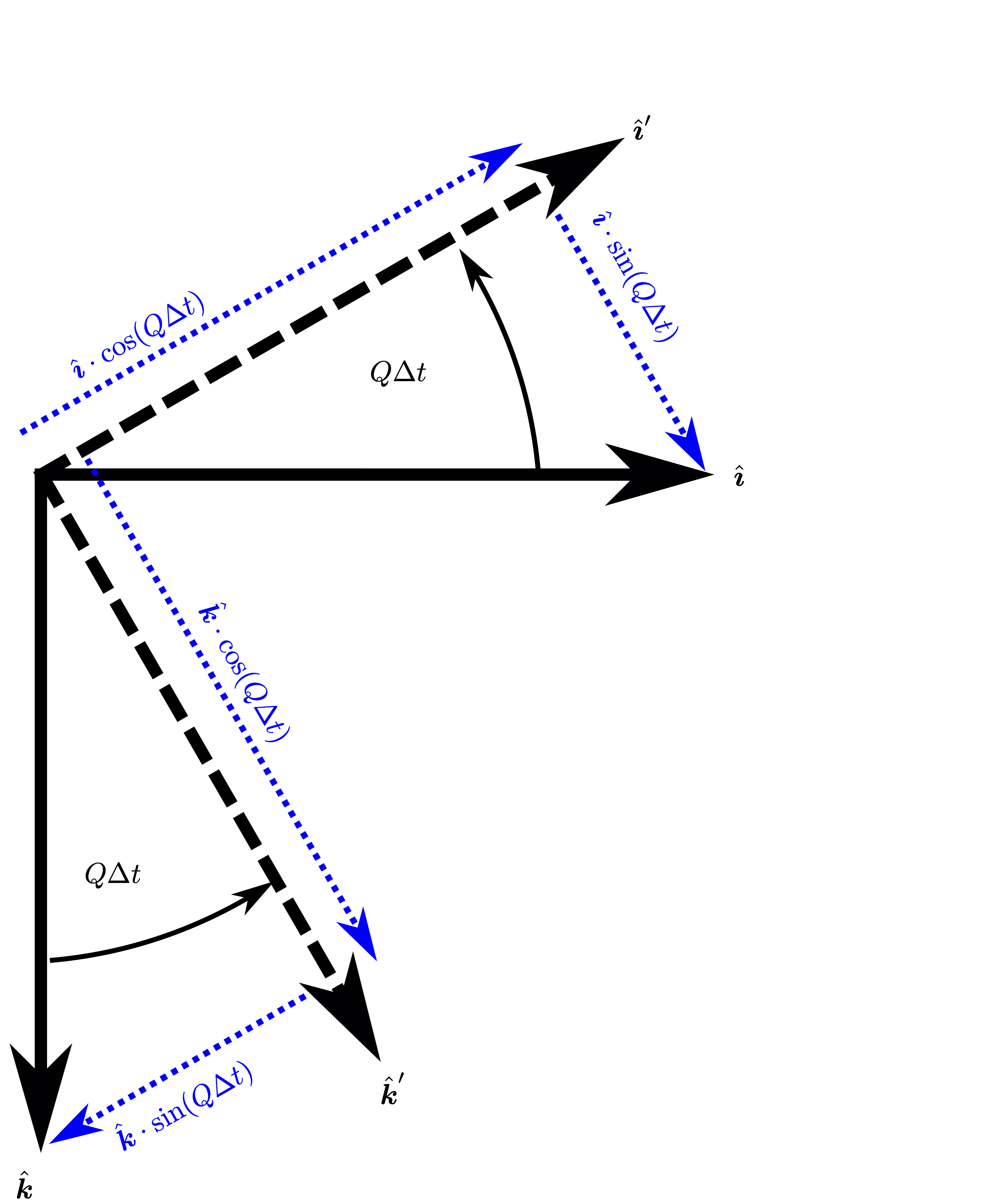

\(\Delta\vec{\boldsymbol{I}}_P\) - change to unit vectors due to body pitch, \(Q\)#

Fig. 51 Change to unit vectors due to pitch rate \(Q\)#

similarly

again, small angle

and thus we can define the \(\Delta\hat{\mathbf{I}}\) due to pitch rate:

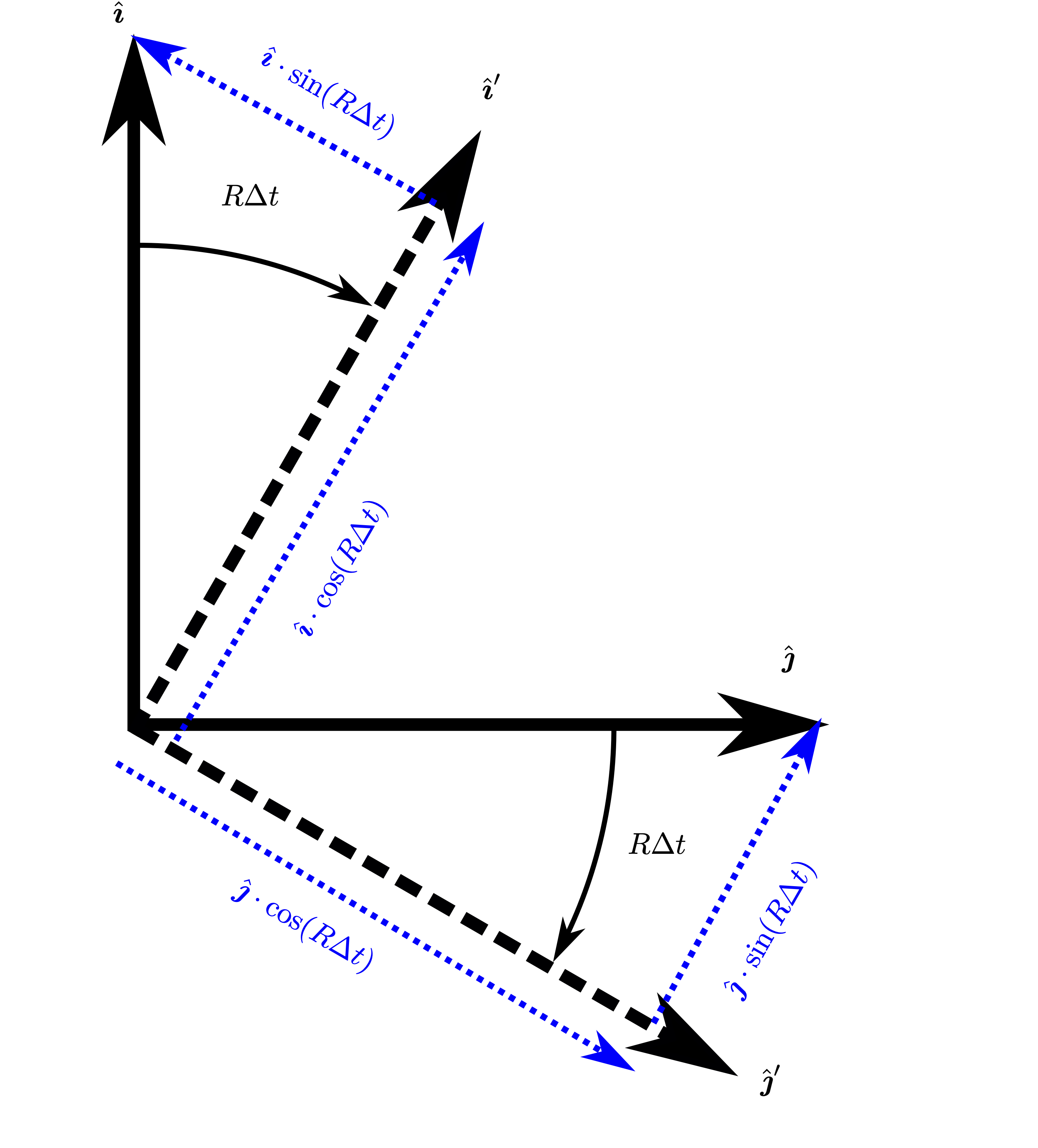

\(\Delta\vec{\boldsymbol{I}}_P\) - change to unit vectors due to body yaw, \(R\)#

Fig. 52 Change to unit vectors due to yaw rate \(R\)#

similarly

again, small angle

and thus we can define the \(\Delta\hat{\mathbf{I}}\) due to yaw rate:

Total change#

The total change is the sum of all three angular components, i.e.,

So the apparent motion due to combined angular rates may now be written

which, in vector form may be written

although the cross product above won’t be used right here, it serves to show that the apparent velocity terms comprise cross-couplings.

Now all the terms in Equation (24) can be expressed in terms of basis vectors and angular rates. So:

may now be populated

and in vector form:

which may be written as

which in general form is

the first order Coriolis identity - and can be used to yield absolute acceleration from a velocity vector, or absolute velocities from a position vector.

Sometimes the second order Coriolis identity is required, as we’ll see - and there are two ways of yielding it:

Differentiate Equation (24) again and yield the following, Eqn (27).Then get the \(\ddot{\hat{\textbf{I}}}\) terms by substituting \(\dot{\hat{\textbf{I}}}\) into Eqn (26), then populating Eqn (27) turning into matrix form

The second way is a little easier - you can basically substitute Eqn (26) into itself.

Try either way - both ways you should yield

which is the second order Coriolis identity

Relative Motion of a point on the aircraft#

In the general form of relative motion derived in the preceding section. We can use a relative motion approach to derive expressions for the absolute aircraft velocities based on data measured at a location away from the aircraft centre of gravity.

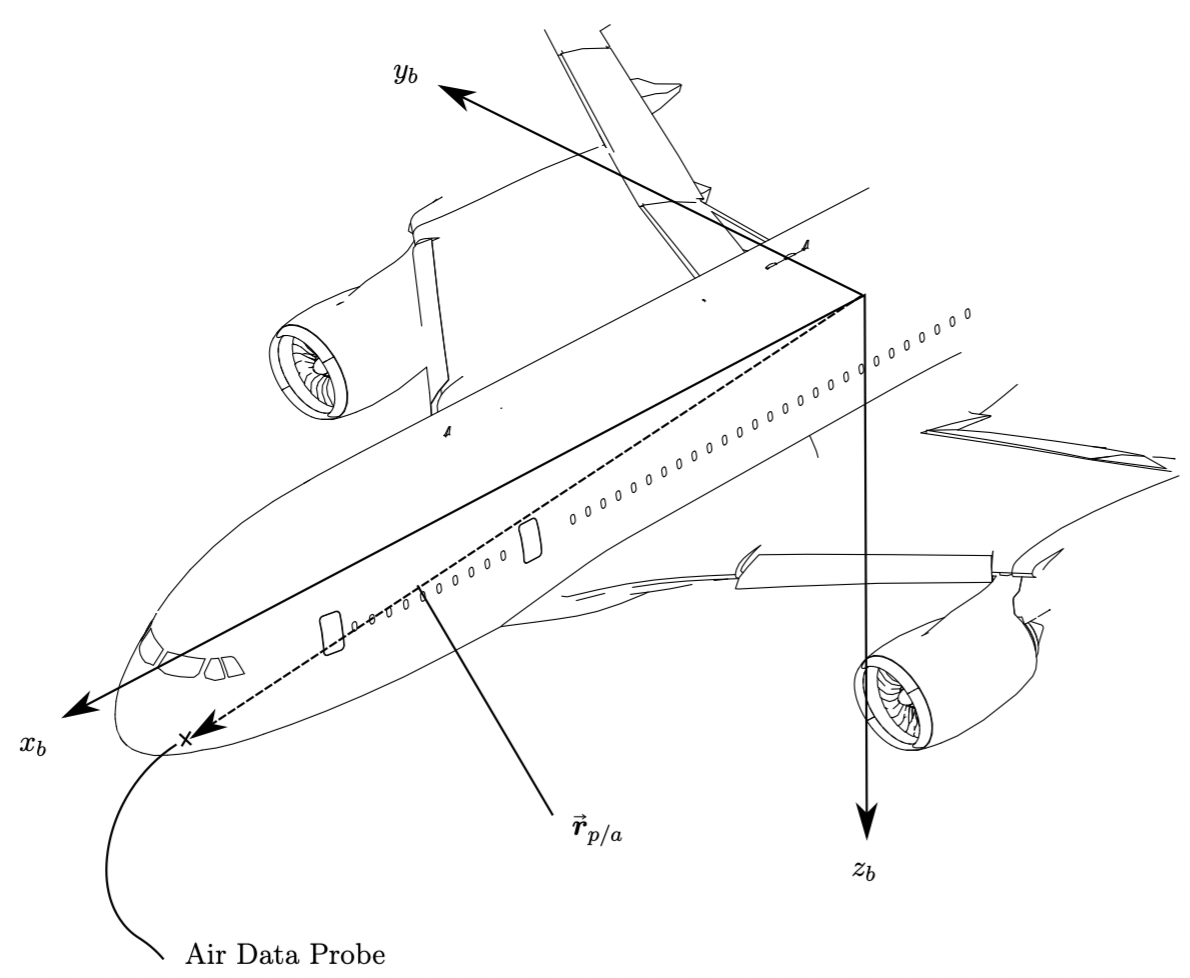

Fig. 53 Air data probe in aircraft axes#

Consider an aircraft with a co-ordinate system located at its centre of mass, and an air data probe located on a the nose at location \(\vec{r}_{p/a}=\left[x_p,y_p,z_p\right]^T_b\), measured in body axes, Figure Air data probe in aircraft axes. Since this the location in body axes, the position vector is the relative position of the probe to aircraft axes.

That is, if the aircraft position is \(\vec{r}_a\) in the absolute reference frame, the the absolute position of the probe is

The air data probe measures angle of attack, sideslip, and total velocity - all at the location of the probe. From what we have learned about relative motion, we know that these will not be the same as those for the aircraft centre of mass, so we need a means to convert these measured values back to aircraft absolute velocities - for use in Flight Mechanics. We denote the quantities measured at the probe as \(\alpha_p, \beta_p, V_{fp}\), and what we desire is \(U,V,W,V_f,\alpha,\beta\).

Expressions are required for the absolute velocity as measured at the probe, so we start with the vector expression for the absolute position of the probe (its position in earth axes).

the absolute velocity is the time derivative of this

the first term above is simply the aircraft absolute velocity, \(\vec{V}_a=\left[u,v,w\right]^T\), and the second term we get from the Coriolis identity

where the first set of terms represents and change in the probe position in aircraft axes

rearranging for the aircraft absolute velocities gives

which gives us the aircraft absolute velocity as a function of those measured at the probe, its position, and the aircraft angular rate (which would be measured at a rate gyroscope in the aircraft). However, we do not have \(U_p,V_p,W_p\), we have the local aerodynamic angles and the total velocity, so we need to develop expressions for them using the definition of total velocity and the aerodynamic angles

hence now we may write expressions for the total aircraft velocity

and the aircraft angle of attack may be developed from the standard aerodynamic angle definitions.

The terms \(\dot{\vec{r}}_{p/a}=\left[\dot{x}_p, \dot{y}_p, \dot{z}_p\right]^T\) represent a velocity due to any change in position of the probe in aircraft axes - that is due to aircraft flexibility.